A new Windows-focused information stealer dubbed “Sryxen” is drawing attention in the security community for its blend of modern browser credential theft and unusually aggressive anti-analysis protections.

Sold as malware-as-a-service (MaaS) and written in C++ for 64-bit Windows, Sryxen targets browser secrets, Discord tokens, VPNs, social accounts, and crypto wallets, then exfiltrates everything to its operators via the Telegram Bot API.

Unlike macOS stealers that typically aim to phish a password and unlock the system Keychain, Windows stealers must contend with the Data Protection API (DPAPI), which ties decryption keys to the logged-in user.

Run as the victim, DPAPI happily decrypts protected data; run as anyone else, the data is useless. Sryxen embraces this model, running in the user context to extract DPAPI-protected material, then layering on a novel trick to handle Chrome’s latest protections.

The most noted capability is Sryxen’s bypass of Chrome 127’s App-Bound Encryption (ABE) for cookies.

Google’s ABE change was designed to bind cookie encryption to the Chrome application itself, breaking traditional approaches that read SQLite databases and call DPAPI.

Malware Uses Browser Automation

Rather than directly decrypting cookies, Sryxen starts Chrome in headless mode with remote debugging enabled and uses the DevTools Protocol over WebSocket to ask Chrome to decrypt its own cookies.

From Chrome’s perspective, it is servicing a legitimate DevTools request; from the attacker’s perspective, they receive fully decrypted cookie values without ever handling the ABE key or writing decrypted data to disk.

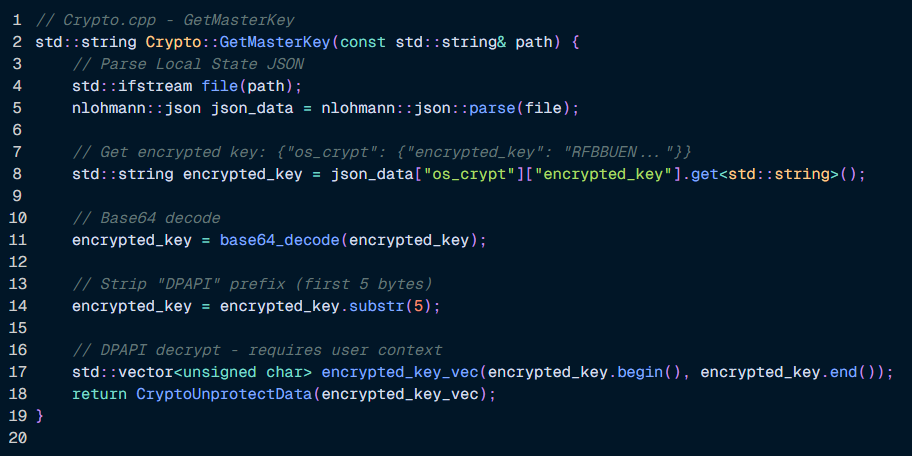

For passwords, Sryxen continues to rely on the established DPAPI plus AES-256-GCM chain used by Chromium-based browsers.

It extracts the master key from the “Local State” file, strips the DPAPI prefix, and calls CryptUnprotectData under the victim’s user context.

Password blobs prefixed with “v10” or “v11” are then decrypted using AES-256-GCM, while legacy formats fall back to direct DPAPI decryption.

Firefox support is implemented via Mozilla’s NSS library, using profile information and key databases to recover saved credentials from logins.json.

Discovery of installed browsers is handled through a multi-threaded filesystem walk, distinguishing Chromium and Gecko-based applications via expected directory structures and configuration files.

Once located, Sryxen harvests passwords, cookies, history, autofill data and bookmarks, as well as Discord tokens in both plaintext and encrypted formats.

Discord’s characteristic “dQw4w9WgXcQ” prefix a tongue-in-cheek reference to the “Never Gonna Give You Up” YouTube ID is used to identify encrypted tokens, which are then decrypted using the same AES-256-GCM and master key mechanism.

Silent Extraction of Cookies and Credentials

On the defensive side, Sryxen’s authors have invested heavily in making static and dynamic analysis difficult. The stealer’s core theft logic resides in a function that is XOR-encrypted at rest and overwritten with illegal instructions.

A vectored exception handler (VEH) decrypts this code only when execution hits those illegal opcodes, then re-encrypts it upon function return using a breakpoint-based mechanism.

This means static disassembly shows only garbage, memory dumps between calls reveal only encrypted bytes, and even live debugging will miss most of the real code unless an analyst steps carefully through the VEH handler.

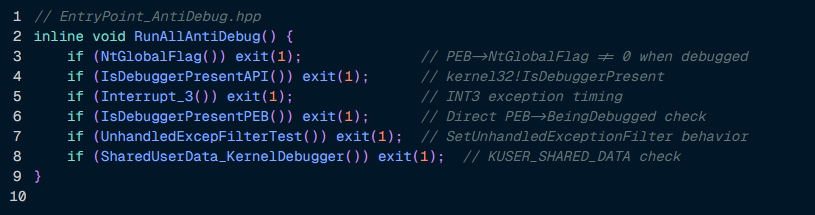

Six separate anti-debugging checks, including PEB flag inspection and kernel debugger status via KUSER_SHARED_DATA, further raise the barrier.

Still, the protections are not flawless. The XOR key is static and embedded in the binary, the pattern of illegal instruction bytes is recognizable, and a patient analyst can recover the decrypted code by single-stepping through the exception handler.

Anti-virtualization is comparatively weak, limited to checking whether Sysmon is running.

Once data theft is complete, Sryxen stages loot in a structured folder tree under %TEMP%Sryxen, organizing text files for passwords, cookies, history and bookmarks alongside directories for social platforms, VPN clients and cryptocurrency wallets and extensions.

From there, it leverages PowerShell’s Compress-Archive command to zip the entire directory and uses curl to upload the archive to a Telegram bot via sendDocument.

This “smash-and-grab” exfiltration model eschews persistence: Sryxen does not stay resident, but its use of system() to invoke PowerShell and curl in sequence creates boisterous process activity a potential boon for defenders monitoring process creation, command-line arguments and outbound connections to api.telegram.org.

For enterprises, Sryxen underscores two realities: browser-centric credential theft on Windows is evolving rapidly in response to platform hardening, and behavioral detection from suspicious headless Chrome launches with debugging flags to automated PowerShell compression and Telegram exfiltration remains a critical line of defense.

Follow us on Google News, LinkedIn, and X to Get Instant Updates and Set GBH as a Preferred Source in Google.