Cybercriminals are increasingly abandoning traditional programming languages like C and C++ in favor of modern alternatives such as Rust, Golang, and Nim.

This strategic shift enables threat actors to write malicious code once and compile it for both Windows and Linux with minimal changes.

Leading this trend is “Luca Stealer,” a newly identified information-stealing malware built entirely in Rust and released publicly as open-source code.

The Rise of Rust-Based Threats

While malware written in Golang has become relatively common, Rust adoption is still in its early stages but growing rapidly.

Luca Stealer marks a significant milestone in this evolution, joining other notable Rust-based threats such as the BlackCat ransomware.

The public availability of Luca Stealer’s source code serves as a blueprint for less experienced cybercriminals, allowing them to study how Rust can be weaponized.

This open-source model accelerates the development of new malware variants, forcing security defenders to adapt their analysis techniques to detect these cross-platform threats rapidly.

Analyzing Rust malware presents unique challenges for security researchers. Unlike standard programs, Rust binaries handle text strings differently, often lacking the “null terminators” that usually mark the end of a sentence in computer code.

According to Binary Defence, this causes analysis tools to misinterpret data, resulting in overlapping text and garbled output.

Furthermore, the Rust compiler organizes code in complex ways, making it challenging to locate the malicious program’s main entry point.

Researchers have found that identifying specific internal functions, such as std::rt::lang_start_internal, is now critical for successfully analyzing the malware’s core behavior.

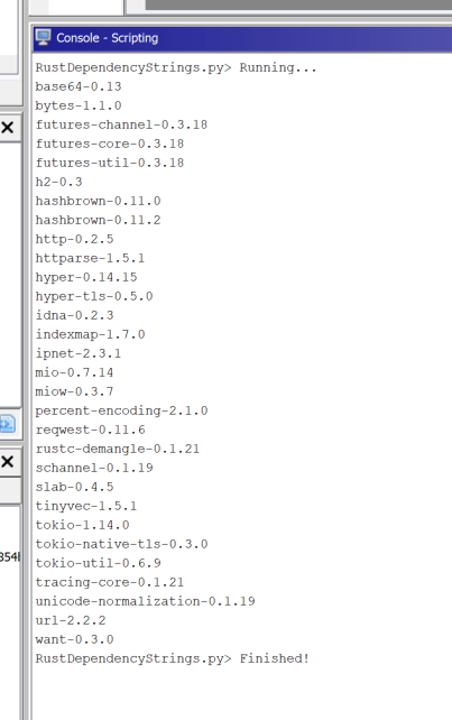

Despite these defensive hurdles, Rust malware leaves behind distinct digital fingerprints that researchers can leverage. The Rust build system, known as “Cargo,” manages external software libraries called “crates.”

When malware is compiled, evidence of these crates is often embedded directly into the final file.

By examining these embedded text strings, analysts can identify precisely which third-party libraries the malware uses.

For instance, the presence of the reqwest crate indicates that the malware can make HTTP requests to steal data.

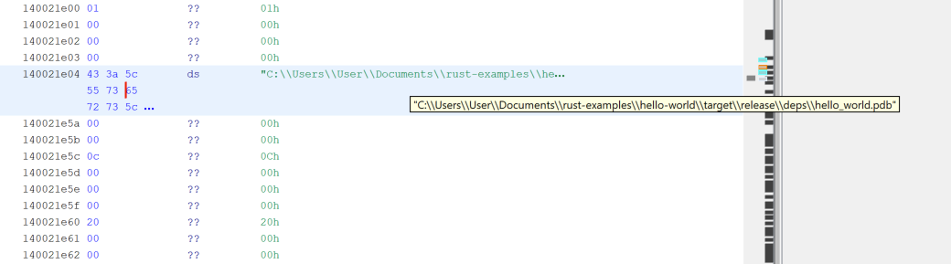

Additionally, careless developers often leave behind “PDB paths” file locations from their own computers that get saved into the malware during the build process.

These paths can reveal the attacker’s username and the directory structure of their development machine.

In a recent analysis of an unknown Rust sample, researchers used these indicators to map out the malware’s capabilities and trace its origins, proving that while Rust malware is sophisticated, it is not invisible.

Indicators of Compromise (IoC)

| Indicator Type | Value | Description |

|---|---|---|

| SHA256 | 8f47d1e39242ee4b528fcb6eb1a89983c27854bac57bc4a15597b37b7edf34a6 |

Rust-based malware sample hash |

| Crate Dependency | reqwest |

Library used for HTTP network requests |

| Crate Dependency | base64 |

Library used for data encoding |

| File Path | librarystdsrcsyswindowsstdio.rs |

Internal Rust library path observed in analysis |

Follow us on Google News, LinkedIn, and X to Get Instant Updates and Set GBH as a Preferred Source in Google.