The UK’s technology sector has had, and continues to have, a significant demographic challenge. As the nation grapples with an ageing population, the UK government has responded with fiscal policies designed to extend the working lives of its citizens, predominantly through the incremental raising of the state pension age.

Simultaneously, the IT sector, the vanguard of the modern British economy, continues to operate within a cultural and structural framework that systematically marginalises older professionals.

The premise of the current UK economic strategy is built on the assumption of “fuller working lives”. With the state pension age having risen to 66 and legislated to reach 67 between 2026 and 2028, the expectation is that workers will remain economically productive well into their late 60s.

For many sectors, this transition, while challenging, is operationally feasible. However, in the technology sector, a “grey door” appears to descend significantly earlier, often as early as age 50, creating a demographic anomaly where the industry most vital to the UK’s future is the least representative of its present population demographic.

The most definitive metric of ageism is the representation gap – the difference between the proportion of older workers in the general economy versus their proportion in the IT sector. According to the BCS diversity report 2024: “There were 446,000 IT specialists in the UK aged 50 and above during 2023, and at 22%, the level of representation for this group was much lower than that recorded amongst the wider workforce (i.e. 30%).”

The report adds: “If the level of representation for older workers in IT specialist positions was equal to that amongst the working-age population as a whole, there would have been 594,000 older IT specialists in the UK during 2023, i.e. approximately 148,000 more than the number recorded.”

This shortfall represents a significant loss of experience, leadership and technical capability, which is particularly ironic in a sector chronically complaining of skills shortages. Beyond the operational strain of the skills shortage, the structural exclusion of 148,000 experienced professionals represents a critical public policy failure, stripping the UK economy of an estimated £1.6bn in lost tax revenue and directly undermining the government’s fiscal agenda for “fuller working lives”.

According to a survey conducted by CW Jobs, “Over a third (41%) of IT and tech sector workers said they have encountered age discrimination in the workplace, whereas only 27% across other UK industries had experienced old ageism.”

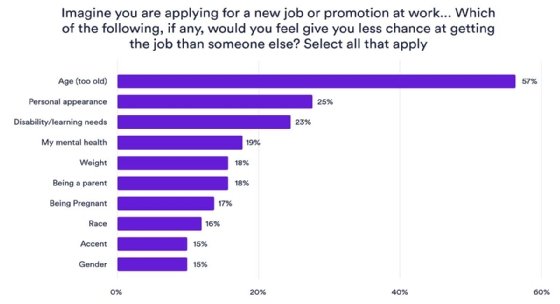

The Stop the bias report 2024 from Tribepad shows similar trends.

The presented trend lines offer little comfort. Despite broader societal trends towards longer careers, the level of representation for older workers in IT roles has remained stagnant over the past five years. While the general employment rate for the “50 to 64” demographic has historically trended upward, the IT sector appears resistant to this shift, maintaining a younger demographic profile as the pool of available young talent shrinks relative to the ageing population.

To resolve the conflict between an ageing demographic and a youth-centric technology sector, stakeholders must move beyond passive acknowledgement of the “grey door” to enact structural reform. When artificial intelligence (AI) tools inadvertently assert human bias, such as ageism, it threatens to turn the government’s “fuller working lives” policy into a driver of inequality.

To prevent the IT sector from becoming a closed shop to the over-50s, the following three recommendations are essential.

1. Mandate algorithmic auditing and glass box transparency

Organisations must treat AI recruitment tools as high-risk systems requiring rigorous safety checks. Companies should implement regular algorithmic audits using counterfactual testing, running identical CVs with different age markers to detect bias.

Furthermore, employers should demand transparency from software vendors regarding how their models handle proxy variables such as formatting and vocabulary, ensuring that years of experience are considered an asset rather than a liability.

2. Institutionalise and scale returnerships

While government initiatives like “returnerships” and “skills bootcamps” provide a framework, the industry must lead the execution. Tech companies should formalise corporate returner programmes as a standard recruitment channel, distinct from entry-level intakes.

These programmes should be designed to bridge the confidence and technical gaps for experienced professionals returning from career breaks, validating their transferable skills rather than forcing them to compete directly with graduates for junior roles.

3. Shift from culture fit to skills-based

The nebulous concept of “culture fit” often serves as a smokescreen for affinity bias, allowing hiring managers to reject older workers who don’t match the prevailing demographic.

Recruitment strategies must pivot to a skills-first taxonomy, where candidates are evaluated strictly on their competencies and potential contribution, rather than social similarity. This requires training human recruiters to recognise and override automation bias, ensuring they do not simply rubber-stamp the rejection of older candidates suggested by flawed AI models.