Phones, smart glasses, and other camera-equipped devices capture scenes that include people who never agreed to be recorded. A newly published study examines what it would take for bystanders to signal their privacy choices directly to nearby cameras.

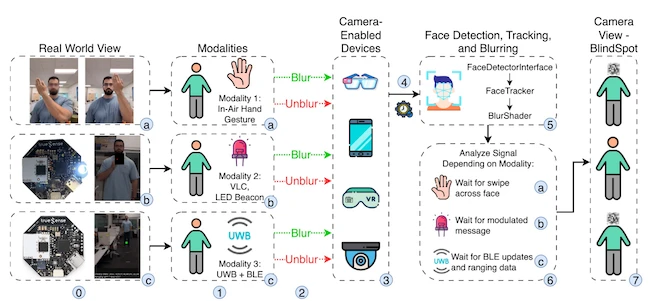

BLINDSPOT system overview

A direct signal from bystanders to cameras

To address this, researchers at the University of California, Irvine designed BLINDSPOT, an on-device privacy signaling system. It allows bystanders to communicate privacy preferences to camera-enabled devices without identity registration, biometric uploads, or cloud processing. The prototype was implemented and evaluated on a Google Pixel smartphone.

BLINDSPOT gives people in a camera’s field of view an explicit way to control how their faces appear in recorded video. When a bystander sends a signal, the device detects and tracks that person’s face and applies blurring before the video is stored or shared.

The system validates each signal by checking whether its physical origin matches the location of a detected face. Signals that fail this spatial consistency check are ignored, reducing accidental triggers and basic impersonation attempts.

Three ways to signal consent

The researchers evaluated three practical ways for bystanders to signal their privacy preference to a camera device. Each method was tested under varying distance, lighting, movement, and crowd conditions, with accuracy measured by whether the system applied the requested blur or unblur action to the correct bystander.

Hand gestures were the simplest option. A bystander swiped a hand across their face to request blurring and reversed the gesture to remove it. This approach required no hardware and worked well at close range. At one to two meters, accuracy reached near-perfect levels, with the device applying the privacy change in under 200 milliseconds.

The second method relied on a small LED beacon carried by the bystander, a light source that blinks in a controlled pattern to send a digital signal. The beacon transmitted a short coded signal that the camera decoded. This approach extended usable range to about 10 meters indoors. Accuracy stayed around 90 percent in normal lighting, with response times just over half a second. False triggers remained at zero across tests.

The third signaling method relied on ultra-wideband radio, a short-range wireless technology that can measure distance and direction very precisely. A bystander carried a UWB tag that communicated with the camera device using Bluetooth and brief ranging exchanges. This method performed consistently across lighting conditions and handled multiple people at once. Accuracy often exceeded 95 percent, with no false triggers observed.

Across all three methods, the study showed that real-time bystander signaling works on consumer smartphones.

Practical limits shape real-world use

Distance is the first constraint. The system depends on detecting a bystander’s face in the camera feed before any signal can be applied. Testing showed reliable operation up to about 10 meters. Beyond that range, faces become too small for consistent detection on a smartphone camera.

Crowd size creates another boundary. Performance degraded once more than eight people appeared in the camera’s view. Processing slowed, latency increased, and frames were dropped. This limit applied across all signaling methods because they share the same on-device video pipeline. Larger groups would require stronger mobile hardware or different processing approaches.

Environmental conditions also limit reliability. Bright outdoor lighting reduced accuracy for light-based signaling, especially at longer distances. Movement in crowded scenes increased error rates for gesture-based signaling. These effects increased variability in performance across uncontrolled settings.

Timing is another factor. Privacy changes were not always immediate. Delays ranged from fractions of a second to roughly two seconds, depending on the signaling method. During that window, recording continued. In brief or fast interactions, this lag may reduce perceived protection.

Hardware availability presents a longer-term challenge. Two of the three signaling approaches require bystanders to carry additional devices. LED beacons and standalone UWB tags are uncommon consumer accessories. The evaluated system relies on dedicated hardware, with broader smartphone-based support described as a future deployment path.

Overall, the findings suggest that bystander controlled privacy is feasible within defined physical, environmental, and scaling limits. Those factors will shape whether the approach moves beyond controlled settings and into widespread use.