A single tap on a permission prompt can decide how far an app reaches into a user’s personal data. Most of these calls happen during installation. The number of prompts keeps climbing, and that growing pressure often pushes people into rushed decisions or choices that feel a bit random. A new research examines whether LLMs can step in and make these choices on the user’s behalf.

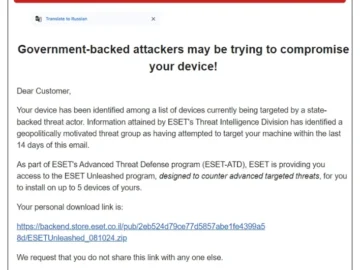

Access control request

How the study worked

The researchers ran an online study with more than three hundred participants and collected over fourteen thousand access control decisions across mobile apps and permissions. All tasks followed Android’s permission model. Participants wrote short statements describing their data-sharing habits, then evaluated permission prompts presented with or without scenario context.

They also reviewed selected LLM decisions and rated whether they agreed with them. This allowed the authors to measure cases where the model produced a choice that users later supported.

The team compared two approaches. Generic models received only the access request. Personalized models received the request and the participant’s statement. Models from several providers were included to avoid reliance on one system.

What the LLMs got right

Generic models matched the majority choice in most tasks. Depending on the model and task type, agreement with users ranged between about 70% and 86%. In essential tasks, where granting access was the expected outcome, the models selected allow in every case.

Models tended to act with more caution in sensitive tasks. They often selected deny, even when some participants selected allow. These decisions reduced exposure to unnecessary data access.

During the feedback phase, participants reviewed model explanations. When participants disagreed at first but read the reasoning, about half changed their judgment and agreed with the model. This suggests that explanations can prompt users to revisit quick decisions.

Where LLMs fall short

Personalization improved results, but not for everyone. Individual outcomes shifted up or down depending on how well a participant’s privacy statement aligned with the decisions they made during the tasks.

Conflicts appeared when a participant’s written statement did not match the choices they selected. When users described their habits in a steady way and made matching choices, the model adjusted without trouble.

Some participants wrote statements that suggested broad approval of requests but then denied a large portion of them. Others described cautious habits and then allowed wide access. When this mismatch occurred, personalized models adapted in ways that reduced alignment.

Security outcomes also changed under personalization. A model that would have denied a sensitive request in its generic form sometimes switched to allow when paired with a permissive statement. The authors note this as a design risk.

A separate risk comes from how explanations influence users. Users often moved toward the model’s judgment after reading its reasoning, including in tasks involving sensitive permissions. This created situations where users supported an unsafe decision after reviewing the explanation.

Limits tied to the study setup

The research took place in an experimental setting, which can shape participant behaviour. They might focus more on each prompt than they would in daily use. At the same time, the choices carried no consequences, which can lead to less careful answers.

The analysis also uses a narrow threat model. Each permission request is treated as a plain input, without testing hostile prompts, crafted examples, or attempts to push the model toward unsafe outcomes. Systems built around LLMs for access control will need further work on how to respond to such conditions and what defenses are suitable.

LLMs bring their own limits. Outputs can shift from run to run, and model use adds cost and delay. Any system that relies on these models must weigh these factors against the burden of repeated prompts and the chance of quick or inconsistent user choices.