A bounty of $12,288 has been announced for the first person to crack the NIST elliptic curves seeds and discover the original phrases that were hashed to generate them.

The bounty will be tripled to $36,864 if the award recipient chooses to donate the amount to any 501(c)(3) charity.

This challenge was announced by cryptography specialist Filippo Valsorda, who raised the amount with the help of recognized figures in cryptography and cybersecurity.

This includes Johns Hopkins University professor Matt Green, PKI and Chromium contributor Ryan Sleevi, browser security expert Chris Palmer, “Logjam attack” developer David Adrian, and AWS cryptography engineer Colm MacCárthaigh.

Background

In Elliptic Curve Cryptography (ECC), seeds are values or sets of values used as the initial input for an encryption algorithm or process to produce cryptographic keys.

ECC relies on the mathematical concept of elliptic curves defined over finite fields to generate relatively short yet secure keys. Using curves ensures that, for a selected point (on them), it’s computationally infeasible to determine the multiple of that point (scalar) used to produce it, providing the basis for encryption.

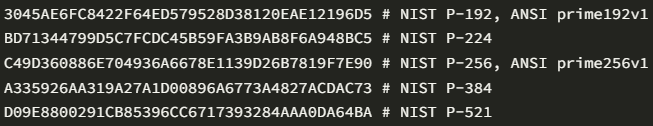

NIST elliptic curves (P-192, P-224, P-256, P-384, and P-521), introduced in 2000 through the agency’s FIPS 186-2 on ‘Digital Signature Standard,’ and which are crucial to modern cryptography, were generated in 1997 using seeds provided by the NSA.

The curves are specified by their coefficient and a random seed value, while the deterministic process to derive the keys is transparent and verifiable to alleviate fears of hidden vulnerabilities.

End users and developers don’t have to interact directly with those seeds but instead, use the curve parameters in the selected cryptographic protocol. However, those concerned with the integrity and security of the system are genuinely interested in the origin of the seeds.

Nobody knows how the original seeds were generated, but rumors and research suggest that they are hashes of English sentences provided to Solinas by the NSA.

Solinas is believed to have used a hashing algorithm, probably SHA-1, to generate the seeds and presumably forgot about the phrases forever.

“The NIST elliptic curves that power much of modern cryptography were generated in the late ’90s by hashing seeds provided by the NSA. How were the seeds generated?,” reads a blog post by Valsorda.

“Rumor has it that they are in turn hashes of English sentences, but the person who picked them, Dr. Jerry Solinas, passed away in early 2023 leaving behind a cryptographic mystery, some conspiracy theories, and an historical password cracking challenge.”

Voices of concern from the cryptographic community started many years ago, starting with the Dual_EC_DRBG controversy that claimed the NSA backdoored the algorithm.

The most worrying scenario arises from speculation and skepticism about an intentional weakness incorporated in the NIST curves, which would enable the decryption of sensitive data.

Even though no substantial evidence exists to support these scenarios, the seeds’ origin remains unknown, creating fear and uncertainty in the community.

Cracking challenge

The security implications that arise from the concerns that the NSA intentionally selected weak curves are dire, and finding the original sentences used to generate them would dispel these concerns once and for all.

Apart from that, this challenge holds historical significance, considering that NIST elliptic curves are foundational in modern cryptography.

Also, this is, essentially, a cryptographic mystery that adds intrigue to the whole story, especially after Dr. Solinas’ death.

Filippo Valsorda believes anyone with enough GPU power and passphrase brute-forcing experience could crack the (presumed) SHA-1 hashes and derive the original sentences.

The first submission of at least one pre-seed sentence will receive half the bounty ($6,144), and the other half will go to the first person who submits the whole package of five. If it’s the same person, they will get the entire bounty of $12k.

More details about the challenge and how to submit your findings can be found in Valsorda’s blog.