There’s a story going around the internet about eBay port scanning its visitors

without any permission or even indication that it’s happening (without digging

into the browser’s developer tools) – it’s absolutely true. But why are they

doing it, and what is eBay doing with the data it collects? I took a peek into

the code to find out (adapted from this thread),

and I’m sure what I found is only a small part of the full story.

The saga began, like many do, with Twitterlings dunking on a brand for cheap laughs.

VPN provider NordVPN shared a post

from blogger Charlie Belmer’s site, NullSweep, entitled “Why is this wbesite port

scanning me?”. Nord

also claimed that browser extensions (presumably theirs), could protect against

“illegal” port scans (they are not illegal). There are tons of people across the

world port scanning the internet daily, both for legitimate research reasons and

to support malicious aims. On the face of it, the claim is absurd, because typical

port scans coming from the internet at large are aimed squarely at any routers,

firewalls, and gateways that join a network to the internet (and servers and PCs

exposed through them) – there simply is no way for a browser, let alone a browser

extension, to sit in the middle and fend off port scanners.

In reality, NullSweep was actually discussing a different type of port scanning,

one initiated directly by a website the target loads in their browser. It’s an

ingenius, if not insidious, technique that allows would-be port scanners to

paradrop straight into an internal network and scan it using Javascript from

within the browser context.

As an aside, this is something that a browser extension could block, however

the company behind the port scanning uses techniques to prevent widespread

blocking of their trackers, as we’ll see later.

How Browser Port Scanning Works

While modern browsers allow Javascript to make requests to other domain names

than the one you’re currently visiting (e.g. www.ebay.com), they layer on

security controls to ensure the target data allows the calling website to access

it. This prevents, for example, a malicious website from requesting the account

details from you bank’s website. However, even without knowing the contents

of the remote site, details about the connection itself (such as the time it

takes to connect or time out) can be used to infer whether or not a website

exists at the given host and port. A bit of Javascript code can wrap that into

a package and allow any site to scan a user’s internal network, determining

which IP addresses and ports have services running. Further, because many

well-known services are commonly available on the same port (there is a

registration page,

but it’s more of a guideline than a hard and fast rule), it’s possible to also

infer some programs that a user may be running on their network depending on

whether the port is open or not.

What eBay’s doing

As noted in NullSweep’s article, eBay is scanning only the user’s local PC,

IP address 127.0.0.1, and looking for a small selection of ports commonly used

by remote desktop software. Interestingly, Charlie tried installing one of those

applications and didn’t notice anything different about how eBay behaved, so

what are they doing with it? I decided to load the site and find out.

Digging into the code

It was at about this time that I found a Twitter post

from Jack Rhysider, host of the Darknet Diaries podcast, on the same topic.

He theorized a number of reasons why eBay might be doing this, and it piqued my

interest even further. In trying to load eBay locally I found that I couldn’t

replicate the behavior in Linux even after spoofing a Windows User Agent and

disabling all of my extensions. There must be some check hidden in the Javascript,

but as of yet I haven’t found one. After that, I loaded a Windows VM, installed

the latest Edge, fired up https://www.ebay.com, and I finally replicated

the port scanning behavior. However, I had some trouble replicating the

behavior reliably, and after some trial and error I found that https://signin.ebay.com/

was far more reliable for triggering the port scanning.

In the browser developer tools I was able to trace the code that launched

the connection to 127.0.0.1 back to a service worker executing a Blob URL.

Blob URLs are a special URL linking to an arbitrary file generated by Javascript,

yet can be used in HTML element hrefs as if it were a link to a static image or

video. In my experience, these are commonly used as a component of DRM schemes

to make it inconvenient (but not impossible) to scrape content like music or

videos from a web page. I don’t know if this was the intention here, but it

certainly added frustration to the debugging process because it meant each scan

origin came from a Blob URL that was randomly generated and different each time

I loaded the page.

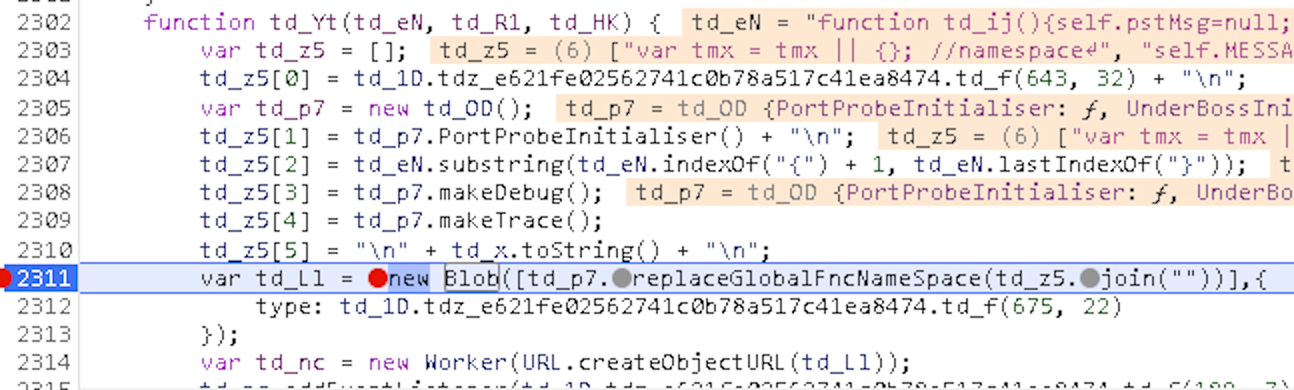

Eventually, I traced the calls to a new Blob(...) constructor and had the

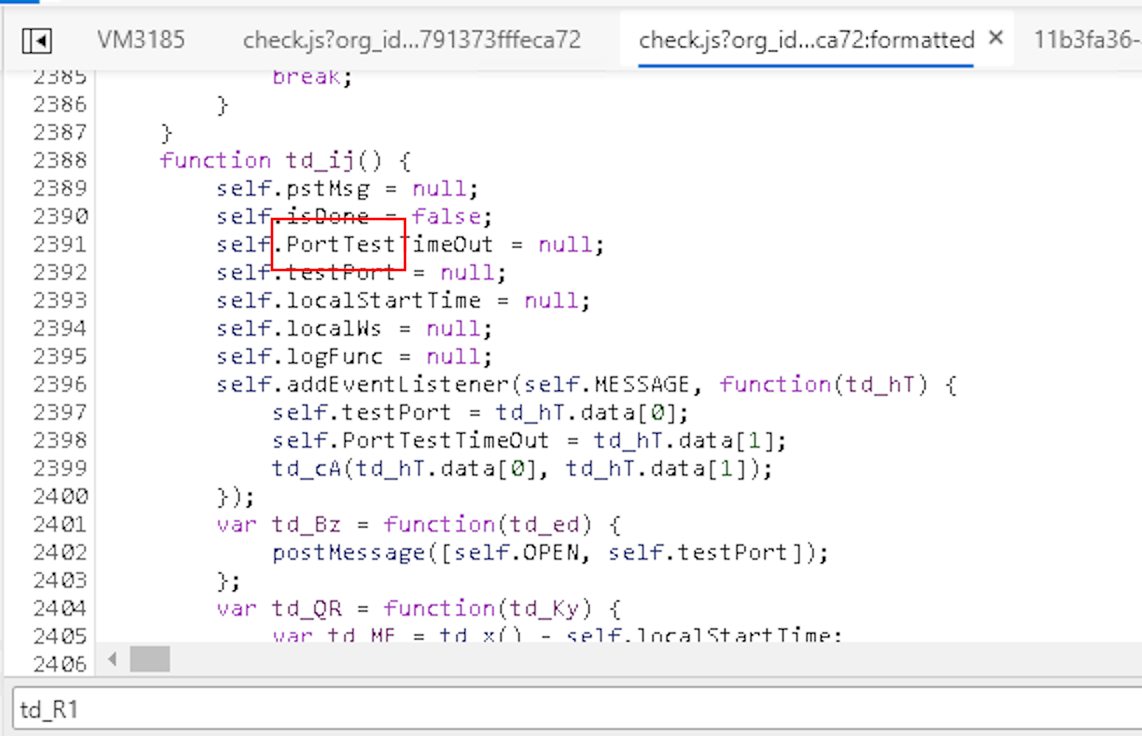

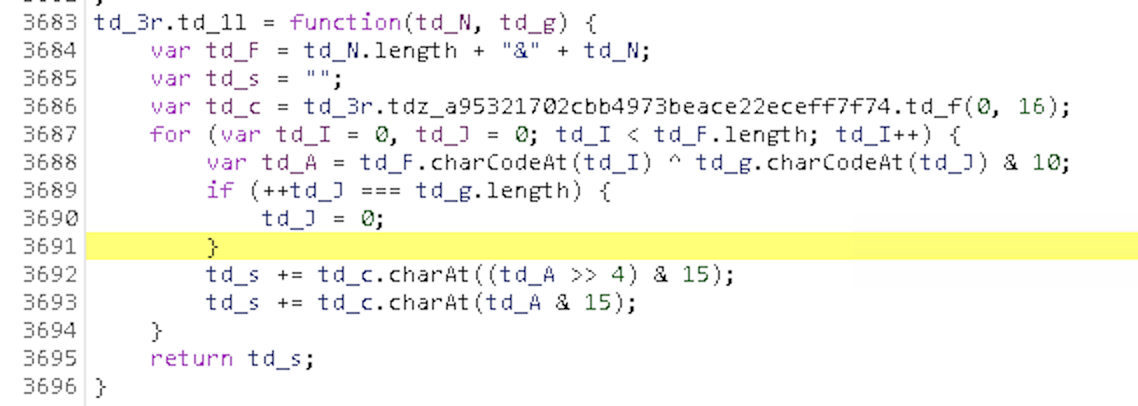

opportunity to set a breakpoint. As you can see in the screenshot below, the

code is heavily obfuscated. td_L1, td_1D, etc. it’s all meant to make

the code difficult to debug and find what’s really happening. Additionally,

and you can’t see it in the screenshot, but all of this Javascript is re-obfuscated

on every page load. A variable named td_L1 now may be named td_9I next time.

This makes it very difficult to retrace your steps if you accidentally refresh

the page because all of the variable names are shuffled around.

Despite the obfuscation, there is nothing truly “magic” about code – it executes

the same instructions that the deobfuscated code would – so with access to a debugger

and judiciously placed breakpoints, you can stop the code at a point in time and

inspect the entire state of the program. Browser debugging tools are truly incredible.

My first order of business was to see how the code for this Blob was generated,

because searching for individual bits in the source did not yield me any results.

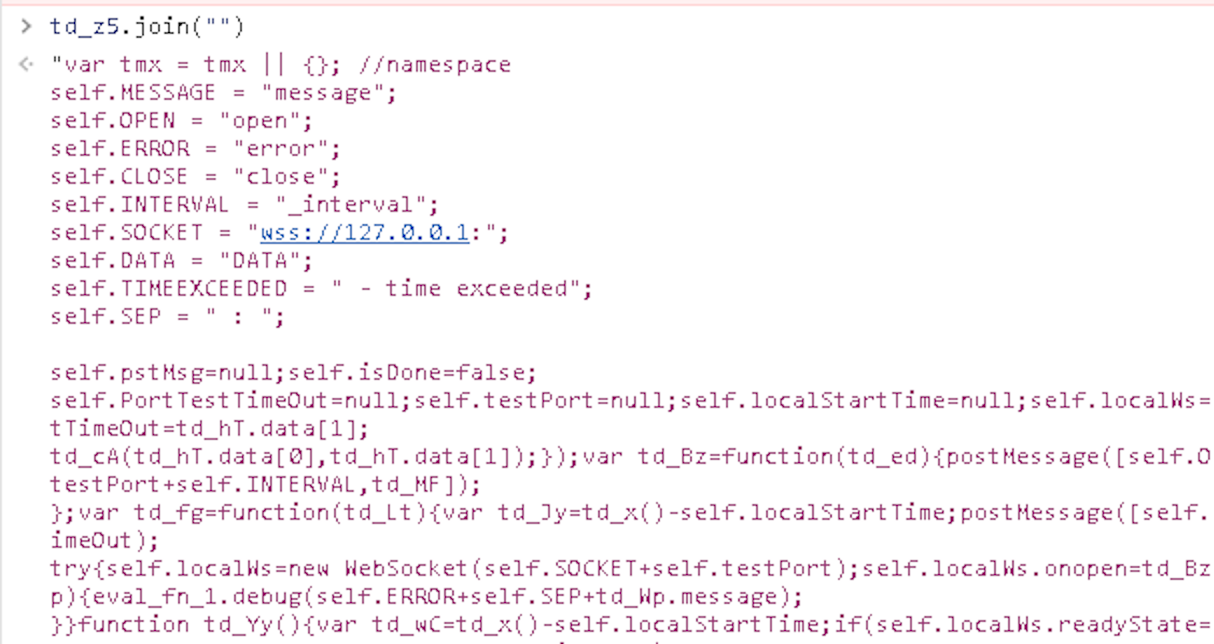

The screenshot above shows a call to td_z5.join(""), which turns an array of

characters into a single string. Now, I’m not a reverse engineer or a malware

hunter, not even an amateur, but I have looked at packed Javascript before

and this technique seems to be a common way to protect code from reverse

engineering (and usually not for good reasons). Again, none of this is illegal,

but it still makes me feel a bit suspicious to know companies are going to such

lengths to hide tracking and scanning data from its customers.

Further on in the code you can see evidence that yes, this is a dedicated port

scanner and not some other (debatably) legitimate reason for eBay to be accessing a

service on localhost (yes, there are cool things you can do with local web

servers, but usually you just see it in the news when

something goes wrong).

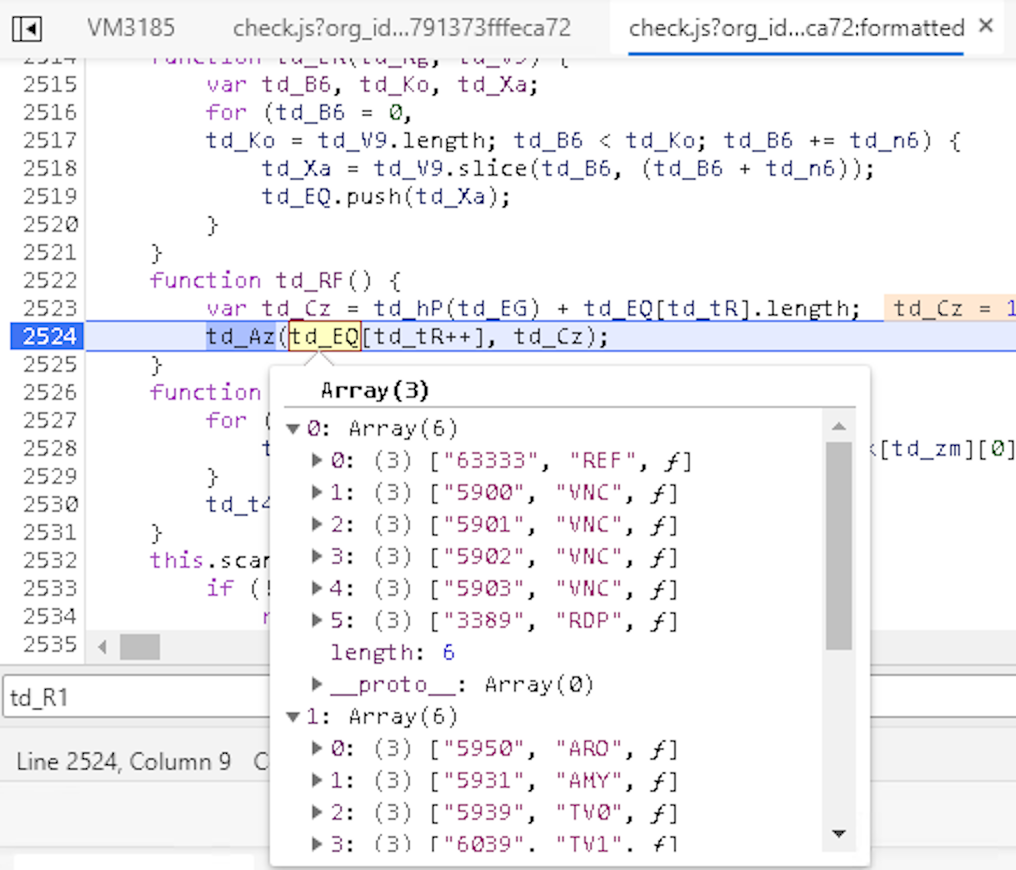

Other variables show specific ports of interest – all related to remote desktop software.

All of this Javascript comes from a script file at a URL like this one:

https://src.ebay-us.com/fp/check.js?org_id=usllpic0&session_id=2398b023c098a9873ec798e

The session ID seems to be randomly generated on each page load, but don’t breathe

a sigh of relief yet – I don’t have high hopes that this means your data is anonymized.

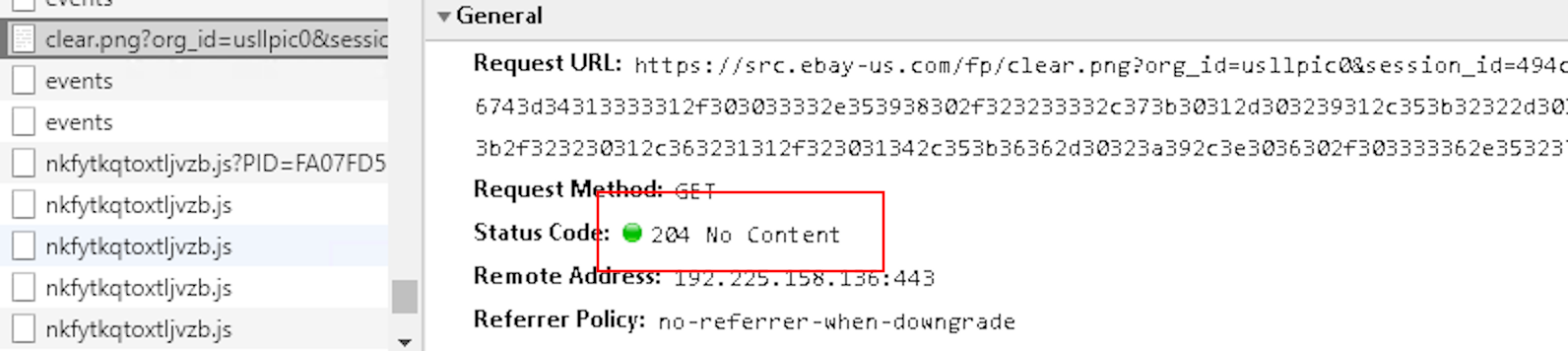

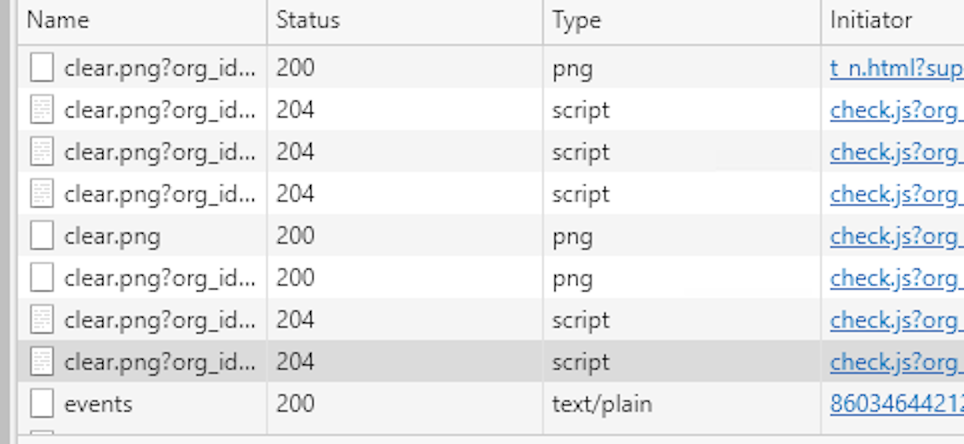

When stepping through the code, I eventually concluded that the results of the

scan were linked to an odd image that was being loaded after all of the scanning

died down. The URL, https://src.ebay-us.com/fp/clear.png, links to the same

domain as the scanning script. This domain isn’t used to load any other scripts

or images, so it seemed like a lead to follow.

Knowing nothing else about the URL, “clear.png” makes me think it might be a

tracking pixel, which are often 1×1 transparent images used to trigger a

signal that someone has viewed the image, yet in the dev tools screenshot

below you can see something kind of odd. The response code is “204 No Content”.

The URL to this PNG isn’t returning an image – it’s returning nothing at all!

If this specific scan was being used for fraud detection, I would have expected

that eBay would receive some sort of fraud score in response to this request,

but it seems the data is simply being tossed to the mother ship for later use.

Or maybe they’re taking a cue from this Russian hacker group,

which uses HTTP status codes as the control protocol itself (just kidding).

Now that we know what’s being done with the collected data, I wondered what,

exactly was being sent to a remote server? The full PNG url looks something

like this:

https://src.ebay-us.com/fp/clear.png?org_id=usllpic0

&session_id=46ab9c371710a4e926a88ae2fffe6d35

&nonce=4b4aa5f76ec76448

&jac=1&je=9834685736a938479283a49328fe429847b93847...

Lots of letters and numbers, could the data be encrypted? Yes, in fact

further research led me to a Javascript function with two variables

passed in:

Here is the code of the function, as copied from dev tools:

After stepping through the code a bit, I was able to identify that it uses bit

shifting and XOR to encrypt the entire payload into a base-16 alphabet (yes,

XOR is a poor encryption method, but plaintext XORed with a key is encryption

nonetheless). I translated the encryption method into Python and then

reversed it to build a decryptor. Follow the gist URL for the full

encryption/decryption implementation. The script can also be run from

the terminal in Python3 to decrypt an encrypted clear.png URL and print the

cleartext payload.

https://gist.github.com/nemec/ea6b21bcd027b81ac1e3fbcfeb01db3e

Relevant decryption bit is replicated here:

def decrypt(encr, key):

alpha = "0123456789abcdef"

message = []

last = None

for idx, (char, keychar) in enumerate(zip(encr, cycle_twice(key))):

if idx % 2 == 0:

last = char

continue

crypt = alpha.index(last) << 4 | alpha.index(char)

message.append(chr(crypt ^ ord(keychar) & 10))

concat = ''.join(message)

length, sep, msg = concat.partition('&')

if len(length) == 0:

return concat

if len(msg) != int(length):

raise ValueError("Error decoding message")

return msg

With a tool for decrypting the exfiltrated data, I set about checking how much

data was being sent out to the src.ebay-us.com domain. There were seven images

in all for one load of the eBay sign in page, and all of them sent different

data.

The data included some personal bits (EU readers may want to check whether they’re

affected and whether or not it adheres to GDPR regulations)

- My user agent

- My public IP address

- Remote desktop port status

- Other data, signatures, and things I don’t recognize

Casting a wide net

To summarize what we’ve found so far:

- eBay collects data on whether certain ports are open on your local PC

- This data is shipped to an eBay domain, but does not seem to be used otherwise

- Additional data like User Agent and IP are also sent

If eBay isn’t using it to decide whether you should be allowed to log in right

there, what is it doing with the data? At this point, I’d stayed up late

and was pretty tired, so I totally missed one hugely suspicious indicator –

the domain where data is exfiltrated is not a subdomain of ebay.com – it’s

ebay-us.com. Still, a quick check shows that it’s owned by somebody at

eBay, so at the very least it isn’t phishing malware. Twitter user Armchair IR

pointed out that similar

behavior has been seen by Facebook and it traced to a company called ThreatMetrix,

an identity tracking/anti-fraud company. Checking the

DNS records

for src.ebay-us.com, sure enough it’s a CNAME to h-ebay.online-metrix.net,

a domain owned by ThreatMetrix Inc.

A search for the domain “online-metrix.net” shows that some people and adblock

extensions have tried banning this domain, which is likely why ThreatMetrix sets

up a customer-specific endpoint and has their customers launder (this is probably

not the correct terminology lol) the domain through one of their own that isn’t

associated with ThreatMetrix.

The earliest record at crt.sh for this domain dates back all the way

to 2013, so it’s possible that eBay has been

scanning customers’ computers for almost seven years without too many people

noticing. online-metrix.net uses wildcard certificates, so unfortunately

it’s not so easy to enumerate their clients, but there is room for further

investigation.

News reports say that LexisNexis acquired ThreatMetrix in 2018,

and their new homepage

talks in general terms about how their data will be used to fight fraud.

They claim that they “analyze more than 150 million daily transactions from

more than 30,000 websites worldwide”, so it seems fair to believe that all of

this data they’re collecting goes straight into one massive database shared

with all of their customers.

In the identity management space, it also seems like the data is definitely not

anonymous:

LexID Digital combines a unique identifier, a confidence score and a

visualization graph to genuinely understand a user’s unique digital identity

across all channels and touchpoints.

Privacy by Design: We uniquely solve the challenge of providing dynamic risk

assessment of identities while maintaining data privacy through the use of

tokenization.

lol

A search for hijacked accounts is probably where some of the port scan

data goes:

Bot and Malware Threat Intelligence: Actionable threat detection for Malware,

Remote Access Trojans (RATs), automated bot attacks, session hijacking and

phished accounts, combined with global threat information such as known

fraudsters and botnet participation.

And, finally, they have a claim called “True Location” which sounds a bit like

they attempt to de-anonymize people using people using VPNs.

True Location and Behavior Analysis: Detection of location cloaking or IP

spoofing, proxies, VPNs, Tor browsers and changes in behavior patterns, such as

unusual transaction volumes.

It’s not just eBay scanning your ports, there is allegedly a network of 30,000

websites out there all working for the common aim of harvesting open ports,

collecting IP addresses, and User Agents in an attempt to track users all across

the web. And this isn’t some rogue team within eBay setting out to skirt the law,

you can bet that LexisNexis lawyers have thoroughly covered their bases when

extending this service to their customers (at least in the U.S.).