Families that combine open communication with effective behavioral and technical safeguards can cut the risk dramatically

30 Oct 2025

•

,

6 min. read

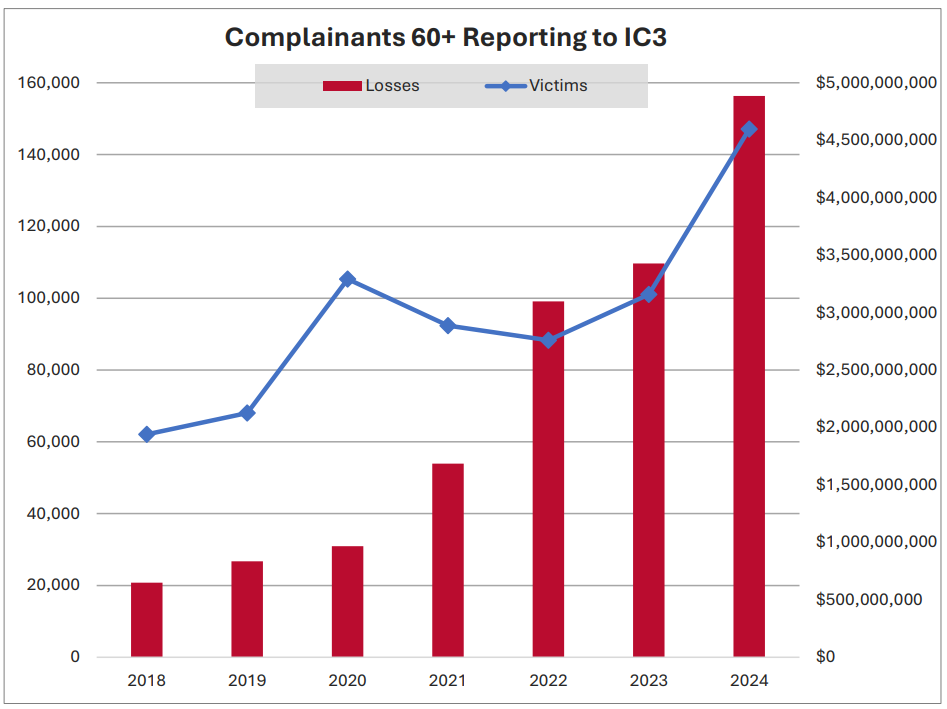

When we talk about fraud that can inflict a severe financial and emotional toll on the victims, it’s not hyperbole. One area where this is increasingly evident is elder fraud, as the amounts of money lost to various kinds of online scams climb sharply every year.

In 2024 alone, Americans aged 60+ reported almost $4.9 billion in losses to online scams, an increase of 43 percent from the year prior and a five-fold increase from 2020, according to the FBI’s Internet Crime Center. The average loss from elder fraud was $83,000, compared with $19,000 across all age cohorts.

Behind those numbers are individuals and entire families whose well-being and financial security were shaken to the core after years of savings evaporated in a moment of misplaced trust. The sheer scale of fraud targeting the elderly is something that should make families take notice and fight back together.

Vague warnings won’t cut it, however. Effective protection combines ongoing family communication, human and technical controls, and a clear remediation plan if something does still go wrong. As October is Cybersecurity Awareness Month, now is a good time to take stock of how we can help protect our parents’ and grandparents’ savings from scammers.

Why scammers go after the elderly

Scammers are rational operators: they chase profit and low friction. Seniors are attractive targets for several intersecting reasons:

- Access to funds: Many seniors have cash savings, retirement accounts or other stable sources of wealth that fraudsters see as easy pickings.

- Trust in authority: Generational habits around trust and authority make some older adults more receptive to calls or letters that pose as “official.” Many seniors are unlikely to question a call from “the bank” or “the IRS”.

- Loneliness: Social isolation can make relationship-based scams, such as dating scams, devastatingly effective.

- Cognitive overload and digital fatigue: Many seniors (let’s face it: not just them) have a hard time managing dozens of online accounts, which makes them more likely to fall for “helpful” popups or urgent phone calls.

- Technology gaps: Many seniors use older devices and outdated software, the same passwords across accounts and, just like everyone else, often struggle to tell the real from the fake.

These are all basic conditions that can make the attacker’s job easier. In addition, handy attackers have handy tools at their disposal, including large databases of compromised credentials available in underground forums to AI-driven voice cloning, that conspire to raise the “credibility” of their ploys.

The scammer playbook

Here are a few schemes that pay great dividends to scammers targeting older people:

Phishing scams

Scammers can pose as IRS, Medicare or bank representatives, demanding payment to avoid penalties or to “unlock” accounts. These schemes often push victims to enter their login credentials or disclose other sensitive information on websites that are designed to resemble those belonging to legitimate entities.

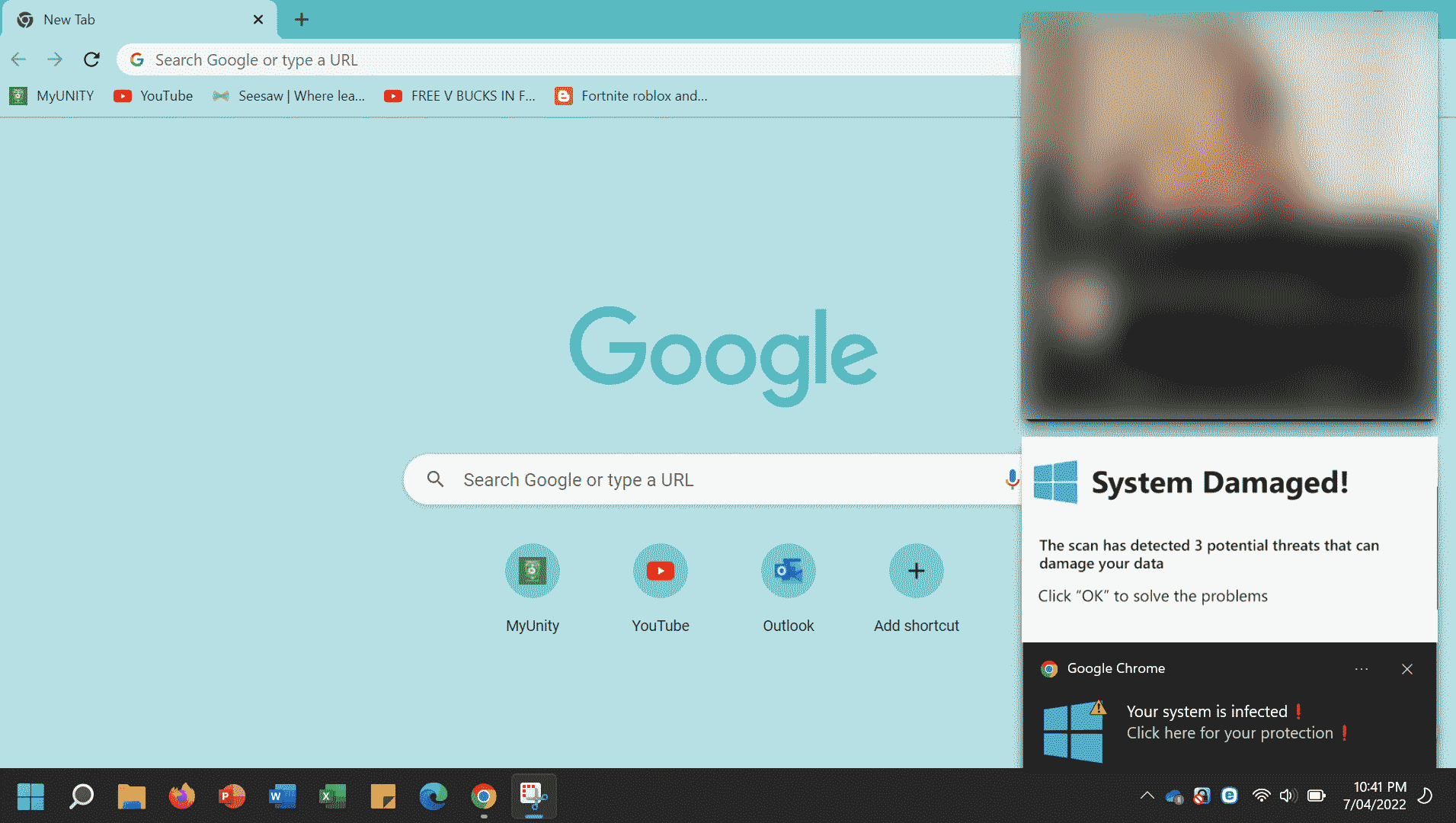

Tech support fraud

A warning popup on a computer screen or a phone call claims that your device has been compromised with malware. The “support” rep convinces you to grant remote access, then steals banking credentials or installs infostealer malware on your device.

Romance scams

Fraudsters cultivate relationships with their “marks” over periods of time spanning weeks or months, earn their trust, and then request large wire transfers for a fabricated emergency.

Grandparent scams

A caller claims that your loved one is in trouble and urgently needs money wired. As the ask preys on emotions, victims often skip verification and oblige with the request, sending the money requested via wire transfers, gift cards, or money-transfer apps. These methods are often effectively irreversible.

Investment scams

Fraudsters sell fake investments, such as crypto schemes or high-yield “private” offerings, using fabricated endorsements from well-known figures.

As fraudulent schemes increasingly leverage deepfakes, scammers can clone other people’s voices or craft videos that appear to involve family members or trusted public figures, making many of the ploys feel alarmingly real.

Starting a conversation

Scams are long known to invoke a sense of urgency, authority and scarcity to trick people into taking action. Even a momentary lapse in judgement, cognitive overload, stress and sleep deprivation can magnify our susceptibility to scams, which is ultimately why prevention is at least as much behavioral as it is technological.

One important layer of defense can be laid with open, shame-free communication. Start with empathy and explain how scammers manipulate emotions – if they can trick tech-savvy people in their 30s and 40s, anyone can become a victim.

Or share a story: “A friend of mine has almost wired a ton of money after hearing what sounded like her grandson’s voice. It turned out to be a scam. Can we make a family rule that before sending money, we’ll always double-check?”. In other words, consider implementing a simple plan built around “pausing and verifying” so that at least one other family member is the go-to “verification buddy” for any financial requests.

Also, if your parent’s or grandparent’s bank offers special protections for older customers, use them. These may include verification calls for some types of transactions, limits on new payees or holds on big wire transfers, and alerts sent to both the grandparent and a trusted family member for any transfer above a particular threshold.

Basic device and account cyber-hygiene

The steps above are best combined with measures that can close commonly-exploited technological gaps. Make sure your older relatives:

- use a password manager to generate and store a strong and unique password for each online account, especially the valuable ones (e.g., banking, email and social media),

- while you’re at it, turn on two-factor authentication wherever you can, ideally with a mobile authenticator app or even a hardware key, rather than via SMS messages,

- block popups and robocalls using security tools or measures available from phone carriers, as appropriate,

- turn on automatic updates for all devices, especially phones, tablets, and computers,

- remind your relatives not to download attachments or click on links in unsolicited messages – when in doubt, they can use ESET’s free, easy-to-use link checker,

- install reputable security software on all their devices.

Consider going through these steps with your parent or grandparent, and leave clear (and if needed, written) instructions.

If the worst happens

Speed is often of the essence. The sooner you act, the greater the chance of recovering funds or at least stopping further theft. If your (grand)parent falls victim:

- Freeze transfers immediately: Make sure your relative’s bank is “in the know” so it stops any outgoing transfers.

- Document everything: Save phone numbers, emails, or screenshots associated with the scam.

- Report it: File a complaint with the FBI’s Internet Crime Complaint Center (IC3) and the FTC’s IdentityTheft.gov portal.

- Lock down credit: Place a credit freeze to prevent new credit accounts from being opened in your (grand)parent’s name.

- Provide emotional support to your relatives: Remind them that they’re victims of a crime, rather than blame them. Shame keeps people silent, which ultimately only helps scammers.

Final thoughts

For long-term peace of mind, consider also identity monitoring services that alert you if your (grand)parent’s social security number or login credentials surface on the dark web. Build a routine that involves reviewing bank balances, auditing transactions, and revisiting account security settings on a regular basis. At the end of the day, prevention is a habit.

The bottom line is, scams targeting seniors are rising in cost, frequency and sophistication. But families that combine open communication with effective behavioral and technical safeguards can cut the risk dramatically. Put these protections in place and you’ll make it far harder for criminals to turn your (grand)parents’ life savings into their payday.