By Jordan Cadzow and James van Rooyen

Introduction

The uncomfortable truth of our modern digital lives is that infostealer malware has become one of the most pervasive and damaging threats in the global cyber landscape. This point has been showcased in sources ranging from Verizon’s 2025 Data Breach Investigations Report (DBIR), IBM’s X-Force Threat Intelligence Index 2025 and in the KELA Cyber Threat Intelligence report. Recently the record-breaking leak of over 16 billion passwords (https://cybernews.com/security/billions-credentials-exposed-infostealers-data-leak/) in June 2025 linked in large part to infostealer infections shows just how embedded this threat class has become in the broader cybercrime economy.

For Australian organisations, the implications go far beyond IT hygiene. Infostealers now fuel a shadow economy of access brokers, ransomware cartels, and business email compromise (BEC). Understanding how this threat has evolved and where it is heading is crucial for organisations to ensure their defensive cybersecurity capabilities are keeping pace with the attackers of today.

What is Infostealer Malware?

Infostealers are malicious programs designed to harvest sensitive data from infected systems. They commonly target:

- Login credentials (usernames, passwords, tokens)

- Financial data (credit card details, online banking credentials)

- Browser artefacts (cookies, autofill data, saved sessions, histories)

- Personal information (identity data, contacts, documents)

Once exfiltrated, this data is either monetised directly (fraudulent transactions, identity theft) or sold in bulk through underground forums and Initial Access Brokers (IABs). These brokers supply ransomware affiliates and BEC operators with readymade footholds in corporate networks.

According to the 2025 Verizon DBIR, 32% of breaches globally involved stolen credentials, often sourced through infostealers. This places them alongside phishing and vulnerability exploitation as top breach vectors.

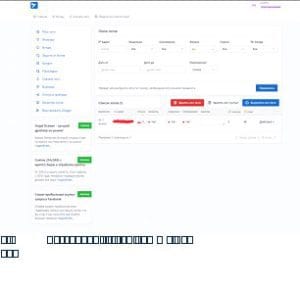

Figure 1 – Screenshot of the Lumma panel provided by the malware authors

The Rise of Malware as a Service (MaaS)

One reason infostealers have become so widespread is the MaaS model, where developers rent their tools for a subscription fee. Take Lumma Stealer, for example:

- The most tracked info stealer globally in 2024, and the fourth most prevalent malware overall.

- Offers a tiered subscription model, easy to use dashboards, detailed documentation, and customer support.

- Provides readymade infrastructure for data collection, allowing even low skilled actors to launch professional campaigns.

- Pricing can be as low as $90 to $600USD per month, with campaigns achieving high margins for operators.

This ease of entry mirrors earlier shifts in cybercrime; specifically, the Ransomware as a Service (RaaS) boom. As with ransomware, the next step is potentially cartelisation – where competing operators secretly form alliances to limit or eliminate competition and increase their collective profits.

Figure 2 – DragonForce change of brand to ransomware cartel

From MaaS to Cartelisation: Lessons from RaaS

The evolution of DragonForce illustrates where the infostealer ecosystem may be heading. Emerging in 2023 as a RaaS operation based on LockBit and Conti code, DragonForce rebranded in 2024 as a “ransomware cartel”.

This model decentralises power as affiliates operate semi independently, often under their own branding, but rely on DragonForce’s infrastructure, leak sites, dashboards and negotiation portals. In return, DragonForce takes only 20% of ransom revenue, a ratio far more attractive than traditional RaaS models.

For infostealers, the implications are clear:

- Infostealer data fuels cartel operations: credentials harvested en-masse are channelled through initial access brokers, and sold to ransomware affiliates.

- MaaS operators may adopt a similar cartel model: just as RaaS groups embraced franchising, infostealer developers may white label their platforms, letting affiliates run “their own” stealer brands.

- Crosspollination is accelerating: affiliates now bundle infostealers, ransomware, and access sales, maximising monetisation.

In short cartelisation in RaaS is a blueprint for MaaS. As ransomware cartels scale, they increasingly depend on infostealer pipelines to keep their “franchisees” supplied with fresh access.

Franchising and the Rise of Cybercrime-as-a-Service

The rise of franchising in cybercrime has dramatically lowered the technical barrier to entry, allowing even a modestly skilled adversary to outsource every step of the intrusion lifecycle, and global pressures have only intensified this trend. The World Economic Forum reported on the impacts of economic hardship, regional instability, and conflict-driven hacktivism and how these factors have swelled the ranks of individuals willing or compelled to engage in cybercrime. Investigations conducted by Interpol, and the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) into large-scale scam compounds in Southeast Asia show how organised crime syndicates industrialise online fraud through call-centre-like operations, complete with scripts, CRM systems, and cryptocurrency cash-out pipelines. The result is a broader, more international base of offenders who can quickly join the cybercrime ecosystem as affiliates.

This dynamic means defenders must assume not only an increase in attack volume but also a diversification of threat origins. The franchise model ensures that takedowns of one platform often have only a temporary impact, as operators and affiliates rapidly re-group under new brands. For enterprises and governments alike, disrupting the economic incentives that underpin these ecosystems particularly by reducing payout success rates and targeting service-tier providers remains one of the most effective long-term strategies.

Attackers Stay One Step Ahead

Cyber defence is often reactive, with each defensive improvement triggering a new offensive pivot. We had simple passwords, so attackers used brute force, we then enforced complex passwords, attackers-built rainbow tables as an adaption, we rolled out MFA, attackers shifted to infostealers harvesting session tokens and bypassing MFA.

This cycle demonstrates a fundamental truth: attackers continually adapt their tradecraft to bypass the control of the day.

The rise of MaaS and RaaS cartels follows the same pattern. Centralised ransomware operations were disrupted by law enforcement in 2024 (e.g. LockBit takedown). Instead of collapsing, actors pivoted into cartel structures with decentralised resilience. Infostealers are undergoing a parallel transition, embedding themselves more deeply into the ecosystem rather than fading.

Cybercrime as CI/CD: Industrialised Innovation

What ties these trends together is that cybercrime increasingly mirrors legitimate software development practices:

- Continuous Integration/Continuous Delivery (CI/CD): Just as software firms push rapid updates, infostealer and ransomware developers iterate quickly, releasing new variants, features, and dashboards.

- Affiliate feedback loops: Cartels and MaaS groups gather feedback from affiliates, fixing bugs, improving obfuscation, and adding features almost in real time.

- Franchise expansion: The franchising of DragonForce shows how “products” (malware) can be distributed like retail brands, with centralised logistics and local operators.

This industrialisation means that defences based on static assumptions (signatures, fixed MFA methods) will always lag. Attackers are organised for agility.

What Comes Next?

If infostealers are today’s problem, what is tomorrows? Several trajectories are plausible:

- Post-MFA Exploits: Expect greater emphasis on session hijacking and identity provider compromise, rather than credential theft alone.

- AI-Augmented Stealers: Generative AI could supercharge malware by evading behavioural detection and tailoring phishing lures with near human precision.

- Data Extortion as a Service: Just as ransomware split into encryption + extortion, expect dedicated extortion cartels built purely on infostealer outputs (think: bulk resellers of medical or financial datasets).

- Cartel Consolidation: The turf wars between DragonForce and rivals like RansomHub suggest a future of mergers and acquisitions, resulting in criminal “supercartels” spanning ransomware, infostealers, and IAB markets.

In effect, cybercrime is following the trajectory of corporate ecosystems: consolidation, franchising, product diversification, and accelerated R&D.

Why Businesses Should Care

For Australian enterprises, these dynamics mean:

- Credential theft is not just an IT issue. It feeds directly into ransomware, BEC, and supply chain compromise.

- Response windows are shrinking. Data stolen by infostealers is often monetised within hours, not days.

- Attack attribution is harder. Cartel structures mask which affiliate or tool was used, complicating incident response.

- Third party risk is rising. Cartel scale credential harvesting means attackers increasingly compromise via suppliers or partners.

Practical Steps to Reduce Risk

While no silver bullet exists, organisations can materially reduce risk:

- Deploy phishing resistant MFA (e.g. FIDO2 passkeys) to blunt token theft attacks.

- Adopt zero trust architecture, with least privilege and continuous verification.

- Harden endpoints by banning cracked software, monitoring for infostealer artefacts, and enforcing patch discipline.

- Expand threat intelligence feeds to include infostealer logs and exposure monitoring.

- Invest in user awareness especially around downloads and phishing.

Conclusion

Infostealers are not an isolated threat; they are a keystone of the modern cybercrime economy, powering ransomware cartels and BEC alike. The shift from simple malware to MaaS, and from RaaS to cartelisation, shows how quickly attackers pivot and professionalise.

Just as businesses embrace CI/CD for software delivery, criminal groups are adopting the same model for malware innovation. The lesson is clear: attackers will remain one step ahead unless organisations anticipate the next pivot and build adaptive, identity centric defences. Security is a constant process of improvement, and maintaining good security posture in the face of organised and evolving threats requires embracing the continuous development and advancement of controls and countermeasures that can keep pace with complex, intelligent attackers.