State-sponsored North Korean hacker group Kimsuky (a.ka. APT43) has been impersonating journalists and academics for spear-phishing campaigns to collect intelligence from think tanks, research centers, academic institutions, and various media organizations.

The warning comes from multiple government agencies in the U.S. and South Korea who are tracking the hackers’ activity and analyzed the group’s recent campaigns and themes used for attacks.

A joint advisory from the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), the U.S. Department of State, the National Security Agency (NSA), alongside South Korea’s National Intelligence Service (NIS), National Police Agency (NPA), and Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA), notes that Kimsuky is part of North Korea’s Reconnaissance General Bureau (RGB).

Also known as Thallium and Velvet Chollima, Kimsuky has conducted large-scale espionage campaigns supporting the national intelligence goals since at least 2012.

“Some targeted entities may discount the threat posed by these social engineering campaigns, either because they do not perceive their research and communications as sensitive in nature, or because they are not aware of how these efforts fuel the regime’s broader cyber espionage efforts,” reads the advisory.

“However, […] North Korea relies heavily on intelligence gained by compromising policy analysts […] (and) successful compromises enable Kimsuky actors to craft more credible and effective spear-phishing emails that can be leveraged against more sensitive, higher-value targets.”

Spear-phishing as journalists

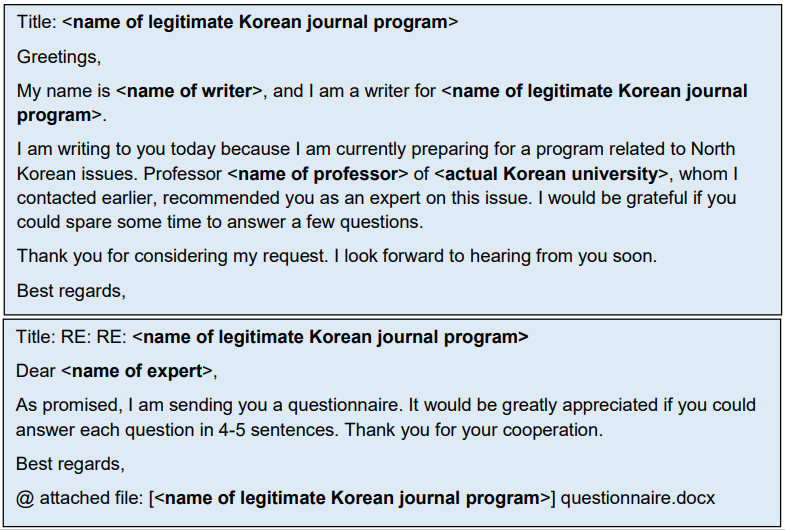

Kimsuky hackers meticulously plan and execute their spear-phishing attacks by using email addresses that closely resemble those of real individuals and by crafting convincing, realistic content for the communication with the target.

“For over a decade, Kimsuky actors have continued to refine their social engineering techniques and made their spear-phishing efforts increasingly difficult to discern,” warns the advisory.

In many cases, the hackers impersonate journalists and writers to inquire about current political events in the Korean peninsula, the North Korean weapons program, U.S. talks, China’s stance, and more.

Among the themes observed are inquiries, invitations for interview, an ongoing survey, and requests for reports or to review documents.

The initial emails are usually free of malware or any attachments, as their role is to gain the target’s trust rather than achieve a quick compromise.

If the target does not respond to these emails, Kimsuky returns with a follow-up message after a couple of days.

The FBI says that despite the adversary’s efforts, the English emails sometimes have an sentence structure and may contain entire excerpts from the victim’s previous communication with legitimate contacts, which had been stolen.

source: U.S. Government

When the target is South Korean, the phishing message might contain a distinct North Korean dialect.

Also, the addresses used for sending phishing emails spoof those of legitimate persons or entities; however, they always contain subtle misspellings.

How to stop Kimsuky

The advisory provides a set of mitigation measures, which include using strong passwords to protect accounts and enabling multi-factor (MFA) authentication.

Additionally, users are advised not to enable macros on documents in emails sent by unknown individuals, no matter what the messages claim.

The same caution should be applied with documents sent from known cloud hosting services, as the legitimacy of the platforms does not constitute a guarantee of the safety of those files.

When in doubt about a message claiming to come from a media group or journalist, visit that organization’s official website and confirm the validity of the contact information.

The joint advisory recommends conducting a preliminary video call as an effective strategy to disperse any uncertainty of potential impersonation before deciding to engage in further communication.