Threat actors are increasingly abandoning traditional languages like C and C++ in favor of modern alternatives such as Golang, Rust, and Nim.

This strategic shift enables developers to compile malicious code for both Linux and Windows with minimal modifications.

Among the emerging threats in this landscape is “Luca Stealer,” a Rust-based information stealer that has recently appeared in the wild alongside other notable threats such as BlackCat ransomware.

The Rise of Luca Stealer

While Rust’s adoption in the malware community is still in its early stages compared to Golang, it is expanding rapidly.

Luca Stealer represents a significant development as it was released publicly under an open-source model.

This availability provides security researchers with a unique opportunity to study how Rust is used in malicious software design, offering critical insights for future defense strategies.

The shift to these languages requires defenders to develop new analysis techniques to detect and reverse-engineer these sophisticated binaries.

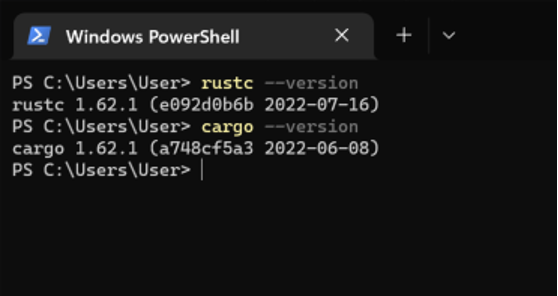

Analyzing Rust binaries presents unique challenges for defenders using standard tools. Unlike standard C programs, Rust executables handle strings differently.

Rust strings are not null-terminated, meaning they do not end with a “null byte” to mark the end of the text. This often causes reverse engineering tools like Ghidra to misinterpret data, leading to overlapping string definitions.

Analysts must usually manually clear code bytes and redefine strings to identify valid data correctly.

Additionally, finding the primary function in a Rust binary requires specific knowledge of the compiler’s output.

According to Binary Defence, the entry point typically initialises the environment and then calls a specific internal function (std::rt::lang_start_internal).

This function receives the address of the actual user-written primary function, which researchers can identify by tracing the arguments passed during this call.

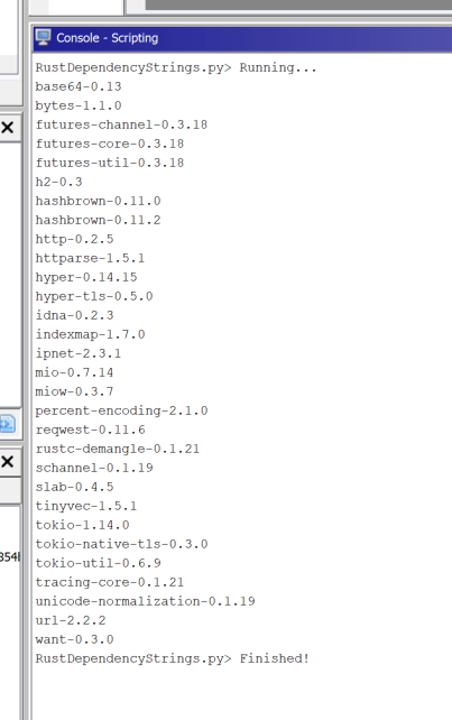

One advantage for defenders is the presence of artifacts left by the Rust build system, Cargo. External dependencies, known as “crates,” are often statically linked into the binary.

By searching for specific string patterns, such as cargoregistry, analysts can list the libraries a malware sample uses, such as reqwest for HTTP requests.

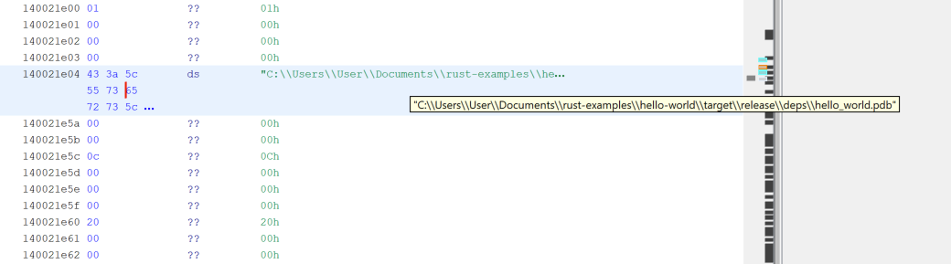

Furthermore, compilation artifacts like PDB paths may remain in the “Debug Data” section, potentially leaking the author’s username or system paths.

As threat actors continue to leverage Rust, understanding these structural nuances is essential for effective detection.

Indicators of Compromise (IoCs)

| Type | Identifier | Description |

|---|---|---|

| SHA256 | 8f47d1e39242ee4b528fcb6eb1a89983c27854bac57bc4a15597b37b7edf34a6 | Unknown Rust Malware Sample |

| String | cargoregistry | Indicator of Rust crate dependencies |

| String | std::rt::lang_start_internal | Indicator of Rust runtime entry point |

Follow us on Google News, LinkedIn, and X for daily cybersecurity updates. Contact us to feature your stories.