Security teams often gather large amounts of threat data but still struggle to improve detection or response. Analysts work through long lists of alerts, leaders get unclear insights, and executives see costs that do not lead to better outcomes. A recent report from ISACA notes that this gap remains wide across enterprises, and explains that organizations collect information at a pace that makes it hard to understand what matters.

The issue is not access to intelligence feeds, but building a program that knows which questions to answer and how to act on the results.

A complex threat environment with fast shifts

Criminal groups run operations that resemble supply chains. Some brokers sell initial access. Others deliver ransomware. Separate groups manage stolen identities and cookies. This creates a broad market with many moving parts.

Infostealer malware collects credentials, cookies, browser data, and other sensitive details from user devices. Attackers then sell this information in large volumes in dark web markets. About 30% of stealer logs come from enterprise licensed environments. Security operations leaders still miss much of this exposure, which gives attackers opportunities to enter networks long before any alert appears.

Ransomware activity shaped by geopolitical conditions and a rise in AI is increasing pressure on programs that need to adjust quickly.

Priority intelligence requirements give structure

Threat intelligence often loses value when it lacks direction. Priority intelligence requirements (PIRs) solve that problem. They define what needs to be learned, why it matters, and what actions depend on the answer.

PIRs ask questions that support decisions. For example, security managers can focus an inquiry on the social engineering techniques used to bypass help desk authentication in similar organizations. This allows help desk teams and identity teams to strengthen procedures in direct response to a known risk.

PIRs also need regular review. Business plans change, technology adoption changes, and geopolitical conditions shift. Threat modeling must reflect these changes. PIRs must follow the same process.

Four types of intelligence that connect to business goals

Cyberthreat intelligence comes in many forms and is based on an enterprise’s risk, threat model, and unique skillsets and specialization. There are four types of threat intelligence that help business and risk leaders match insights to needs.

- Strategic intelligence supports long term planning by reviewing geopolitical trends, regulatory shifts, and industry factors.

- Tactical intelligence examines the techniques attackers use and helps security operations refine controls.

- Operational intelligence focuses on activity that affects the organization itself. Examples include leaked credentials or compromised sessions.

- Technical intelligence supplies indicators of compromise and detection rules that enrich SIEM, SOAR, endpoint tools, web gateways, and firewalls.

Each type speaks to a different audience. Strategic intelligence supports executives and boards. Tactical and operational intelligence help security operations and incident response teams. Technical intelligence supports engineers and analysts. Treating these as separate categories reduces confusion and improves decision quality.

“An effective threat intelligence program is the cornerstone of a cybersecurity governance program. To put this in place, companies must implement controls to proactively detect emerging threats, as well as have an incident handling process that prioritizes incidents automatically based on feeds from different sources. This needs to be able to correlate a massive amount of data and provide automatic responses to enhance proactive actions,” says Carlos Portuguez, Sr. Director BISO, Concentrix, and member of the ISACA Emerging Trends Working Group.

“In order for companies to achieve this, though, they need to overcome challenges like data overload, integration with cybersecurity products, knowledge and experience limitations within their cybersecurity teams, lack of automation initiatives and slow adoption of best practices and security frameworks,” Portuguez continued.

Stakeholder alignment shapes useful PIRs

Product teams, fraud teams, governance and compliance groups, and legal counsel often make decisions that introduce new risk. If they do not share those plans with threat intelligence leaders, PIRs become outdated. Security teams need lines of communication that help them track major business initiatives. If a company enters a new region, adopts a new cloud platform, or deploys an AI capability, the threat model shifts. PIRs should reflect that shift.

This alignment also helps business leaders understand how intelligence work supports growth instead of operating in isolation.

Automation provides scale when data volumes grow

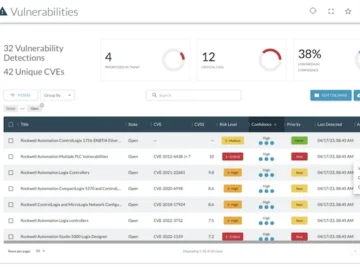

Manual analysis cannot keep pace with the volume of stolen credentials, stealer logs, forum posts, and malware data circulating in criminal markets. Security engineering teams need automation to extract value from this material.

Automation can group stealer logs by risk level, reset passwords when exposed credentials appear, revoke sessions tied to leaked cookies, and score indicators of compromise. Identity teams can use automated workflows to validate whether exposed accounts remain active and trigger remediation without waiting for manual review. Analysts can then focus on decisions rather than constant triage.

AI helps process long blocks of text from criminal forums and identify activity tied to initial access brokers. This saves time and gives threat intelligence teams a view of ongoing trends.

Measurement should tie back to risk reduction

Measuring threat intelligence remains a challenge for organizations. The report recommends linking metrics directly to PIRs. This prevents metrics that reward volume instead of impact.

Examples include the time between collection and distribution of intelligence, the number of fulfilled intelligence requirements, or the percentage of incidents where intelligence provided useful context early in the investigation. These measures relate to outcomes that affect enterprise risk.

Organizations can also track qualitative improvements. For example, intelligence that reduces account takeover attempts or identifies gaps in help desk processes produces value that does not always map cleanly to a single number.

A program that grounds security in threats

Threat intelligence should help guide enterprise risk decisions. It should influence control design, identity practices, incident response planning, and long term investment. When structured around a threat model and PIRs, it informs business leaders rather than distracting them.

Security operations leaders, risk executives, and governance teams all play a role in building programs that respond to threats instead of collecting unused data.