As awareness grows around many MFA methods being “phishable” (i.e. not phishing resistant), passwordless, FIDO2-based authentication methods (aka. passkeys) like YubiKeys, Okta FastPass, and Windows Hello are being increasingly advocated.

This is a good thing. The most commonly used MFA factors (like SMS codes, push notifications, and app-based OTP) are routinely bypassed, with modern reverse-proxy “Attacker-in-the-Middle” phishing kits the most common method (and the standard choice for phishing attacks today).

These work by intercepting the authenticated session created when a victim enters their password and completes an MFA check. To do this, the phishing website simply passes messages between the user and the real website — hence “Attacker-in-the-Middle”.

In contrast, passkey-based logins can’t be phished. Because passkey-based logins are domain-bound, trying to use a passkey for microsoft.com on phishing.com simply won’t generate the correct value to pass the authentication check, even when proxied using an AitM kit.

But attackers haven’t given up that easily. As passkeys become more popular, we’re seeing a number of techniques designed to downgrade or otherwise circumvent the authentication process to make it vulnerable to phishing attacks.

So, here’s all the techniques that attackers have used to get around passkeys (so far).

Downgrade attacks

Downgrade attacks are the go-to method used by attackers to get around phishing-resistant MFA. MFA downgrade functionality has been observed in a number of criminal AitM kits and is even possible using commodity kits like Evilginx.

When conducting an Attacker-in-the-Middle phishing attack, the attacker doesn’t need to relay 100% of the messages accurately. Instead, they can alter some of them. The app might ask the user “You need to MFA — do you want to use your passkey, or your backup authenticator code?”, but the phishing website might modify this page to say “You need to MFA — use your backup authenticator code” not giving you the option to use your secure passkey. This is called a downgrade attack.

This can also be applied to accounts that use SSO as the default login method. In this scenario, the phish kit can select a backup username and password option to allow the phishing attack to proceed.

Here’s an example of Evilginx with a custom phishlet to downgrade authentication for a Microsoft account using Windows Hello.

So, you have a situation where even if a phishing-resistant login method exists, the presence of a less secure backup method means the account is still vulnerable to phishing attacks.

Check out the latest blog post from Push Security to see MFA downgrade in action, real excerpts from criminal phishing kits.

Learn more about how Push detects and blocks MFA downgrade attacks as they happen — in the victim’s browser.

Read our Research

Device code phishing

To get around phishing-resistant authentication methods, attackers are also using device code phishing attacks that take advantage of alternative authentication flows for devices which do not support passkey-based logins, e.g. because they don’t have web browsers, or have limited input capabilities.

This alternative login flow operates by supplying a user with a unique code and instructing them to visit a webpage in a browser on a different device to enter the code in order to authorize the device.

This can be used by an adversary to conduct a phishing attack against a target by convincing them to visit their authentication provider website and enter a code supplied by the adversary, thereby granting access to their account.

This attack has the advantage of linking the target to a legitimate URL, with no prompt to consent to explicit permissions beyond entering the device code and signing in. Additionally, verified apps can be impersonated in some cases.

This technique has been observed in a number of recent campaigns, including repeated Russia-sponsored targeting of M365 accounts (1) (2).

Consent phishing

Consent phishing was one of the first techniques added to the SaaS attacks matrix and has been around for some time, but with a recent uptick in malicious activity.

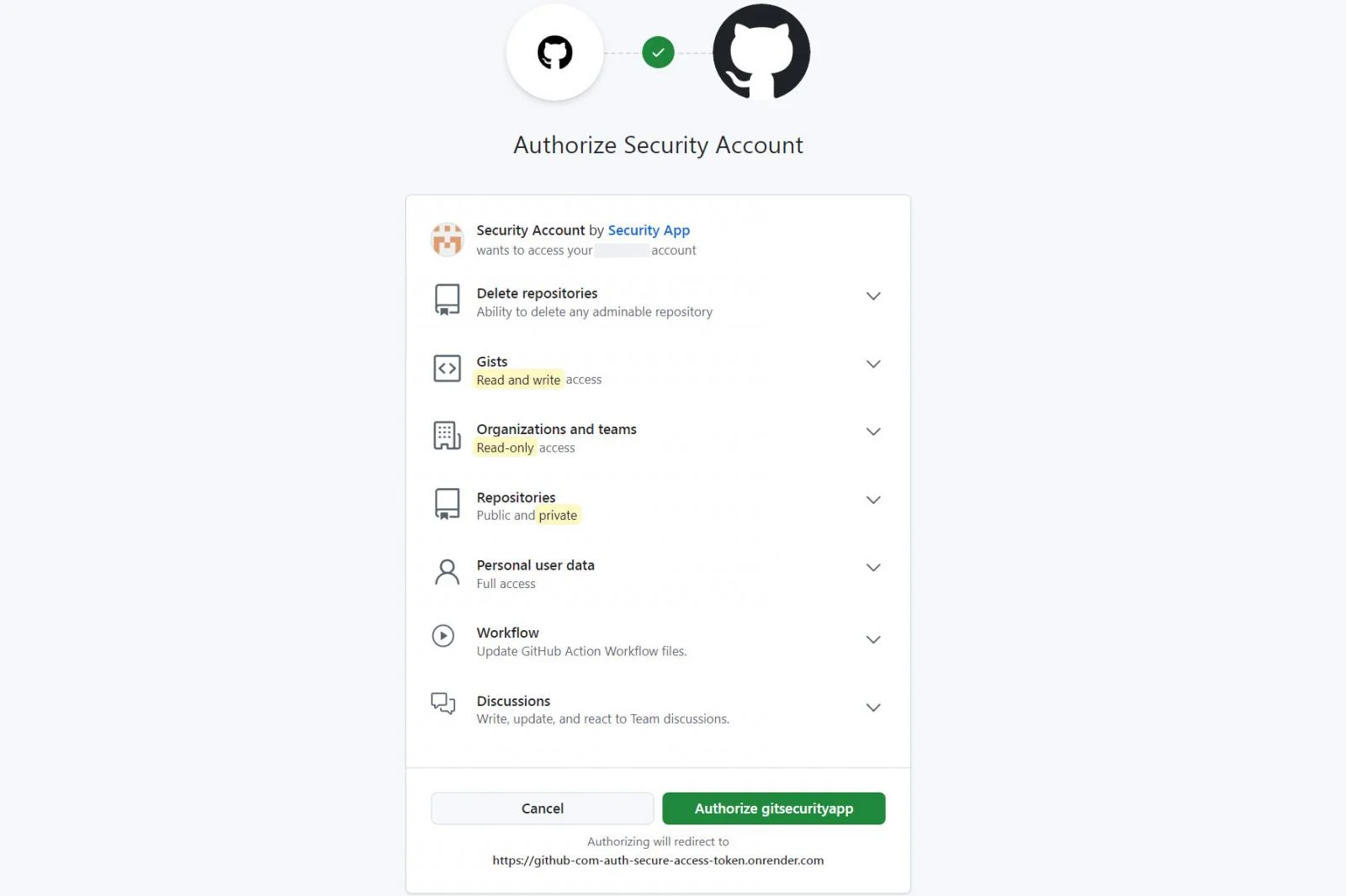

OAuth allows users to grant third-party apps permissions to access their data. Adversaries can abuse this functionality by tricking users into authorizing access for malicious OAuth apps.

In a consent phishing attack, an adversary sends a phishing link to a target that requests permissions to access sensitive data or permissions to perform dangerous actions. If the target grants consent for the permissions, the adversary gains that level of access over the target’s account. This level of access will bypass MFA and persist through password changes.

Consent phishing is most commonly associated with attacks aimed at getting access to Microsoft Azure or Google Workspace tenants. However, it has become more common for SaaS apps to implement their own OAuth-authenticated APIs and app stores that can be targeted in the same way — as seen in this recent example targeting GitHub users.

Once authorized, the attacker has extensive access to the account. In this example affecting GitHub, the attacker would be able to modify repositories to conduct further attacks against users (e.g. by infecting them with malware), poison the repos and services connected to the repository, and exfiltrate any sensitive data the account has access to.

Verification phishing

Email verification is sometimes used as a control, such as when registering new accounts. This is typically implemented by emailing the target user with either a clickable link for them to verify or a verification code that they need to enter.

Verification phishing is when an adversary uses phishing, or some other type of social engineering, to convince a user to click a verification link or pass them the verification code in order to defeat this control.

An example of this technique being used to bypass MFA is with cross-IdP impersonation. This is where an attacker simply registers a new IdP account to the victim’s corporate email domain. In many cases, this allows you to log in via SSO using the new IdP without any further checks — in fact, 3 in 5 apps were found to allow this behavior.

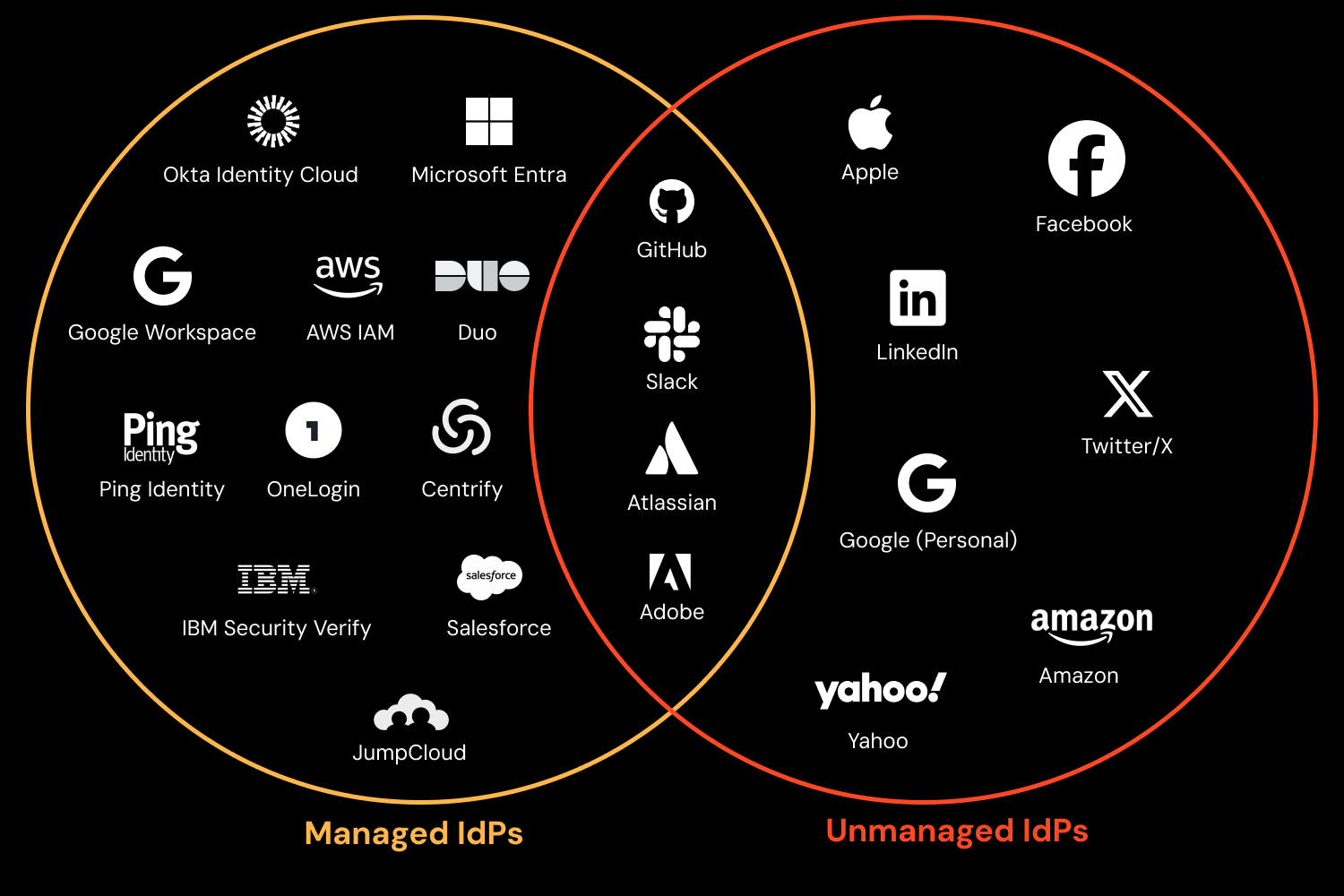

When you consider the large number of apps that can function as an IdP for the purposes of SSO, there are quite a few possible targets (depending on the app, and the login methods it supports).

Managed IdPs can be administered centrally by the organization (which owns and operates the IdP and the identities on it), whereas unmanaged ‘social’ IdPs are controlled by the vendor, and identities are owned and administered by the user.

You can see an example of this in the video below, or read an analysis of two in-the-wild examples here.

App-specific password phishing

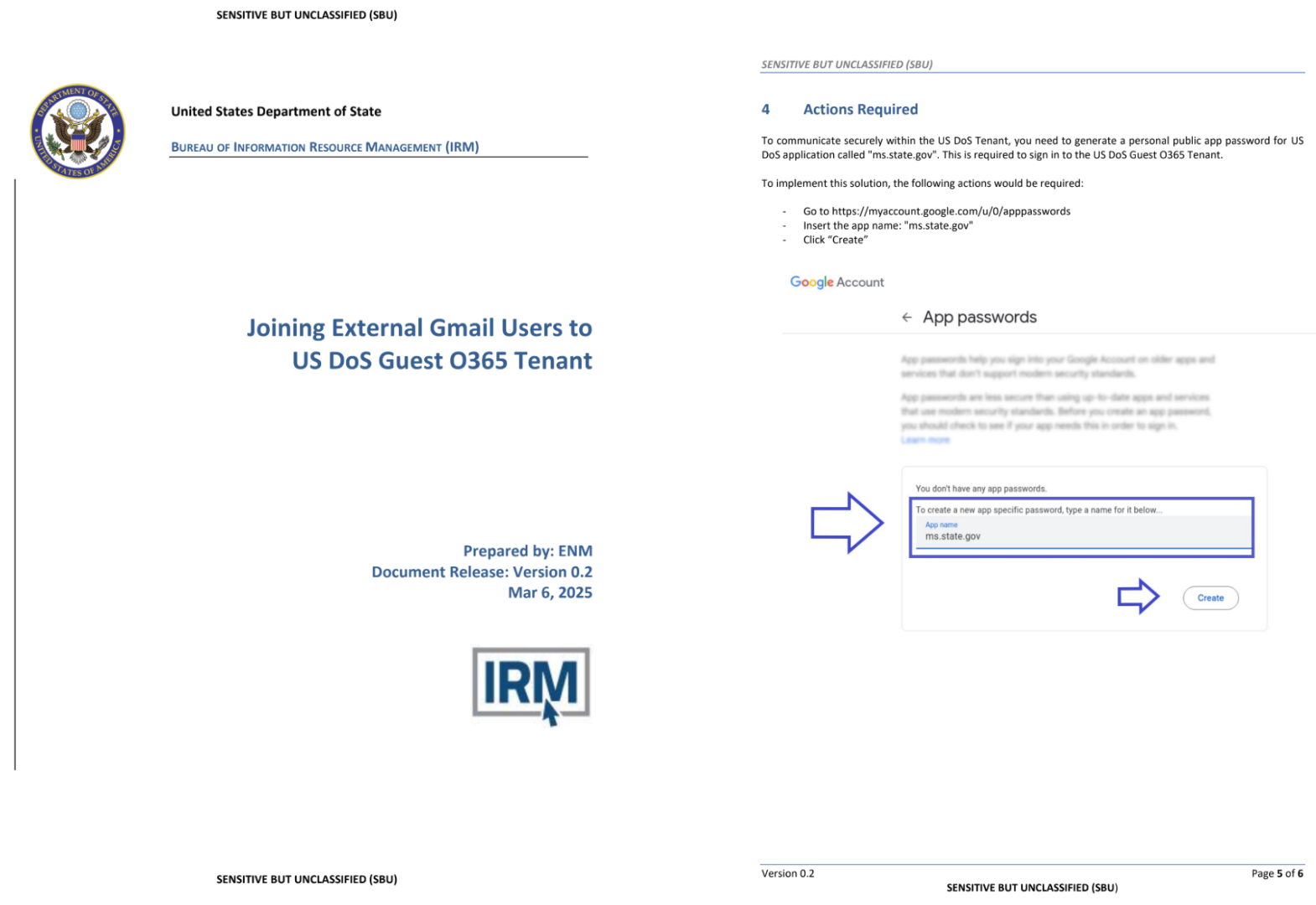

App-Specific password phishing is a social engineering technique where an adversary tricks a user into generating an “app-specific password” for their account and then sharing it with the attacker. These legacy passwords are a feature in some major SaaS providers (like Google and Apple) designed to allow older applications that do not support modern authentication (like OAuth 2.0) to access account data.

The attack flow typically involves a pretext where the attacker, posing as a trusted entity (e.g., tech support, a service provider), directs the user to their account’s security settings. The user is then guided through the process of creating a new app-specific password and is instructed to paste this password into a form or chat window controlled by the attacker.

Because app-specific passwords are designed for use in environments that do not support MFA, once the attacker possesses this password, they can gain persistent, programmatic access to the user’s account data (e.g., emails, contacts, files) via APIs, often without triggering the same level of security alerts as a traditional interactive login from an unrecognized device.

This makes the access stealthier and more durable than a session token, as these passwords typically remain valid until manually revoked by the user.

A recent example of this was disclosed where an expert on Russian information operations was targeted with a sophisticated and personalized social engineering attack, where the attacker was able to establish persistent access to the victim’s mailbox using ASPs by logging into a mail client.

This involved a sophisticated lure impersonating the US Department of State instructing the victim on how to create and share an ASP with the attacker, granting access to their Google mailbox.

Bonus: Targeting local accounts not using passkeys

Possibly the easiest way to get around passkeys, though, is to target apps that don’t support passkeys natively. Passkeys are typically used in combination with SSO, where you log into your primary IdP provider with a secure, passkey-protected login, and then on to connected apps via SSO. Many apps do not allow passkey logins directly.

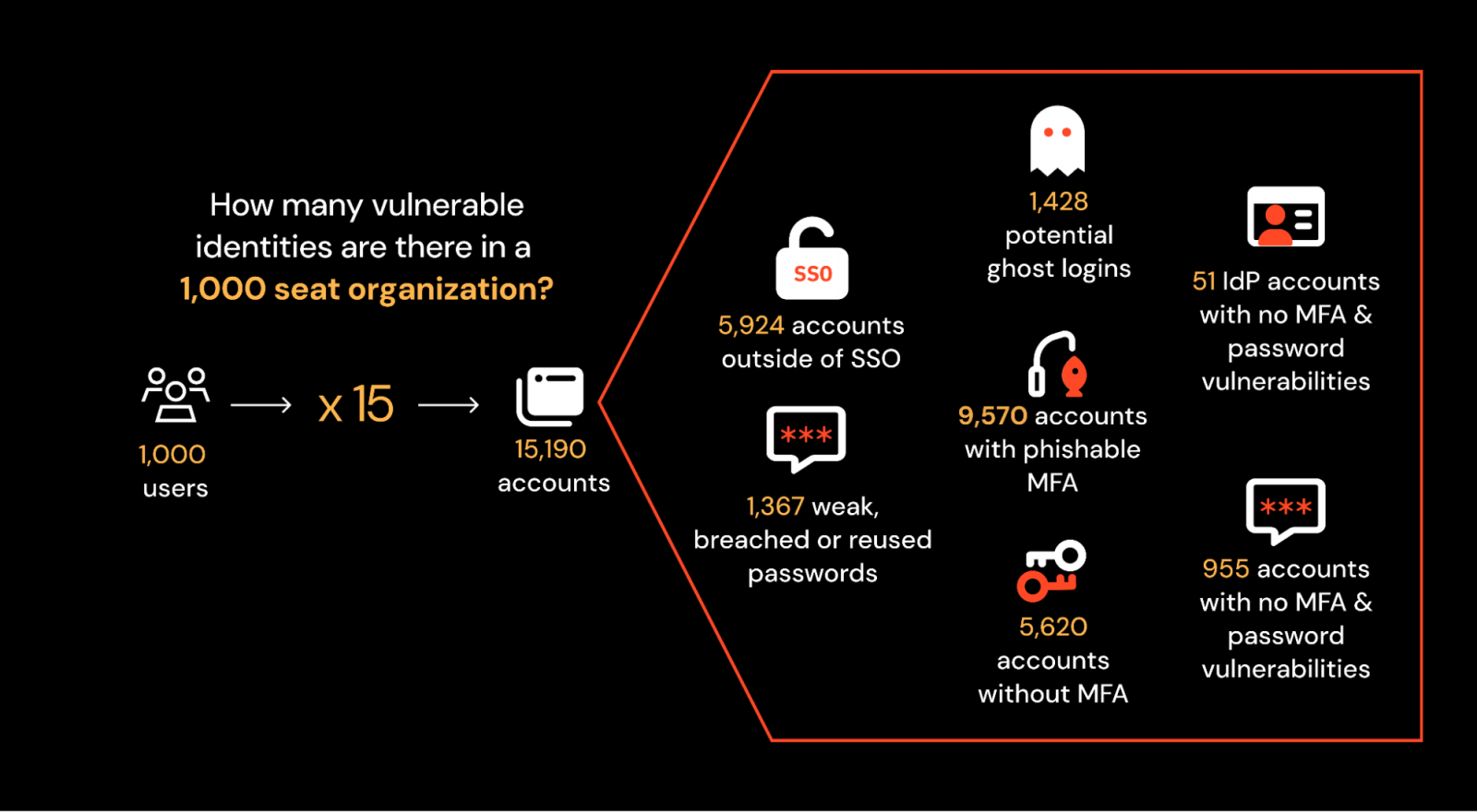

As a result, apps like Slack, Mailchimp, Postman, GitHub, and other commonly-used business apps are being increasingly targeted directly — bypassing IdPs (MS, Google, Okta, etc.) that typically have more robust authentication controls in place.

Just like backup MFA methods are often registered alongside passkeys, local “ghost login” methods are often registered alongside SSO, meaning that accounts have multiple possible entry points.

In many cases, they don’t have MFA deployed at all — making them equally susceptible to attacks using stolen credentials (as seen in the Snowflake attacks last year, and Jira attacks this year).

This results in a vast and vulnerable identity attack surface for organizations to manage.

Conclusion

Most of the time, attackers don’t have to do anything different to get around passkeys. Simply using the same phishing tools and techniques they usually apply will get the job done in the likely event that a backup, non-passkey MFA method is registered to the account.

The only accounts that are truly secure are those with only passkeys, and no backup methods OR conditional access policies preventing non-passkey authentication.

But the devil is in the detail here too (such as this recent example of Microsoft-provided CA templates setting “risky” sign-ins as false positives and allowing them to proceed).

And auditing your app and identity sprawl is no mean feat when you consider the varying levels of visibility and control available to security teams per app (and the fact that many apps are simply not centrally adopted or known to begin with).

Prevent and intercept phishing attacks with Push Security

Downgrade attacks using AitM phishing kits make up the vast majority of passkey-bypassing phishing attacks.

Push Security’s browser-based security platform provides comprehensive identity attack detection and response capabilities against techniques like AitM phishing, credential stuffing, password spraying and session hijacking using stolen session tokens.

You can also use Push to find and fix identity vulnerabilities across every app that your employees use, like: ghost logins; SSO coverage gaps; MFA gaps; weak, breached and reused passwords; risky OAuth integrations; and more.

If you want to learn more about how Push helps you to detect and defeat common identity attack techniques, book some time with one of our team for a live demo.

Sponsored and written by Push Security.