“Threat actors are becoming more advanced, sophisticated, and are constantly changing their tactics.” This mantra has dominated cybersecurity discourse as organizations grapple with escalating breach volumes.

Industry reports typically portray attackers as methodical operators executing flawless playbooks moving seamlessly from initial access to data exfiltration or ransomware deployment.

The reality documented in Windows Event Logs tells a starkly different story.

Recent forensic investigations by threat hunting teams reveal that behind the veneer of “advanced persistent threats” lies a messier truth: attackers frequently fumble commands, encounter unexpected obstacles, and resort to trial-and-error rather than executing predetermined strategies.

Analysis of endpoint detection and response (EDR) telemetry combined with Windows Event Log records exposes threat actors experimenting in real-time, reacting to defensive barriers, and repeating failed techniques.

A November compromise highlighted by security researchers showcased this operational chaos.

While surface-level analysis suggested a smooth progression toward Warlock ransomware deployment, granular examination of Windows Event Logs revealed significant attacker struggles.

These weren’t the actions of an elite cyber operative following a rehearsed script. They were the digital equivalent of someone fumbling in the dark, adjusting tactics based on what succeeded or failed in the moment.

The threat actor repeatedly attempted and initially failed to install Cloudflare tunnels, executed mistyped commands, and tried launching an OpenSSH server despite the application being absent from the compromised system.

Three Incidents, One Persistent Adversary

More compelling evidence emerged from three separate intrusions investigated between November 6 and November 25, 2025.

Security analysts identified identical tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) across all three incidents, along with overlapping infrastructure indicators pointing to a single threat actor or coordinated group.

Each attack originated through web application vulnerabilities that enabled remote code execution via Microsoft Internet Information Services (IIS) web servers.

The adversary’s objective remained consistent: deploy a Golang-based trojan named “agent.exe” to establish persistent access.

Incident 1 demonstrated the attacker’s iterative learning process. When Microsoft Defender blocked their initial certutil.exe-based download attempt, the threat actor didn’t pivot to sophisticated evasion techniques.

Instead, they simply uploaded a renamed executable (815.exe) and attempted to launch it three times before achieving success without even trying to disable Windows Defender.

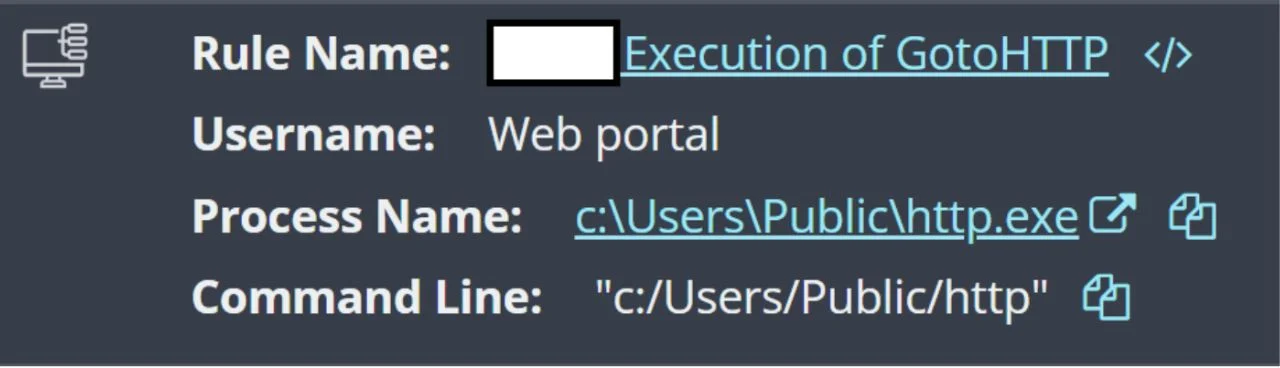

When Defender eventually quarantined agent.exe on December 3, the attacker returned five days later with a rebranded copy of the legitimate GotoHTTP remote management tool, accessing the same vulnerable web application entry point.

Incident 2 showed apparent lesson application. On November 17, the threat actor preemptively added Windows Defender exclusions via PowerShell before deploying malware a direct response to quarantine issues encountered in Incident 1.

However, operational problems persisted: the persistence mechanism (a Windows service named “WindowsUpdate”) failed to start despite multiple attempts, as documented in Service Control Manager event logs.

Incident 3 on November 25 followed an almost identical pattern to Incident 2, including the same Windows Defender exclusion commands and the same service startup failures.

Implications for Defenders

This forensic evidence challenges the narrative of constantly-evolving adversaries. Rather than revolutionary tactical shifts, these incidents demonstrate threat actors implementing incremental adjustments based on previous failures while simultaneously repeating techniques that don’t work.

For security teams, this insight is actionable. Understanding specific friction points failed service installations, quarantine triggers, repeated access attempts enables defenders to identify behavioral patterns and implement targeted countermeasures.

The “sophisticated” attacker may simply be a persistent one who eventually succeeds through iteration rather than expertise.

Indicators of Compromise (IOCs)

| Item | Description |

|---|---|

| C:userspublic815.exe | |

| SHA256: | 909460d974261be6cc86bbdfa27bd72ccaa66d5fa9cbae7e60d725df13d7e210 |

| Incident Details | Executable (Incident 1) |

| IP Address (Attempted Download) | 110.172.104.95 |

| Client/Network Connection IPs | 188.253.126.205, 188.253.126.202, 103.36.25.171 |

| agent.exe & dllhost.exe | |

| SHA256: | 66a28bd3502b41480f36bd227ff5c2b75e0d41900457e5b46b00602ca2ea88cf |

| Incident Details | Executable (Incident 2, 3) |

| VirusTotal Link | Spark RAT Detection |

| test.exe | |

| SHA256: | 272de450450606d3c71a2d97c0fcccf862dfa6c76bca3e68fe2930d9decb33d2 |

| Incident Details | Executable (Incident 2, 3) |

| VirusTotal Link | ShellcodeRunner Detection |

| Client/Network Connection IPs | 188.253.126.202, 103.36.25.169 (Incident 2) |

| Additional IP (Incident 3) | 188.253.121.101 |

Follow us on Google News, LinkedIn, and X to Get Instant Updates and Set GBH as a Preferred Source in Google.