A custom Windows packer dubbed pkr_mtsi is fueling large-scale malvertising and SEO‑poisoning campaigns that deliver a broad range of information‑stealing and remote‑access malware, according to new research.

First observed in the wild on April 24, 2025, the packer remains active and has continuously evolved over the past eight months, while retaining a stable behavioral core that makes it amenable to robust detection.

Threat actors are using pkr_mtsi to wrap trojanized installers for legitimate software, abusing user trust in popular tools to gain initial access.

Observed lures include counterfeit for utilities such as PuTTY, Rufus, and Microsoft Teams, distributed via fake download portals that rank highly in search results through paid malvertising and aggressive SEO poisoning.

While the campaigns mimic legitimate distribution flows, there is no evidence of supply‑chain compromise of the legitimate vendors; instead, the threat hinges on deceptive web infrastructure and poisoned search visibility.

Researchers note that pkr_mtsi functions as a general‑purpose loader, rather than a single‑payload wrapper. Across campaigns, it has been used to deliver multiple malware families, including Oyster, Vidar, Vanguard Stealer, Supper, and others.

Windows Packer pkr_mtsi

This flexibility allows operators to swap or combine payloads with minimal changes to the delivery infrastructure, aligning the same malvertising funnels with shifting monetization goals and partnerships in the criminal ecosystem.

From a behavioral perspective, the packer’s early-stage activity is dominated by memory allocation followed by intensive memory writes to a single contiguous region.

On the defensive side, pkr_mtsi leaves several reliable fingerprints. Antivirus detections that are not purely generic often include substrings such as “oyster” or “shellcoderunner,” and one public YARA rule exists under the name “TextShell,” though it covers only a subset of samples.

Recent research consolidates a broader set of structural and behavioral traits into a comprehensive YARA rule designed to match all known pkr_mtsi variants, backed by retro‑hunting results showing consistent classification under “oyster” and “shellcoderunner”‑type threats.

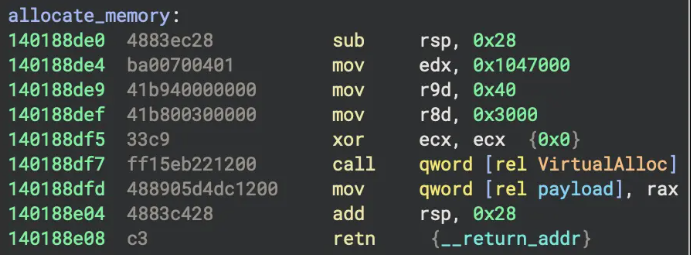

Technically, pkr_mtsi exhibits a distinctive unpacking model. In all observed variants, the first custom function invoked by main allocates memory for the next stage and then reconstructs that stage from numerous one‑ to eight‑byte chunks embedded as immediate values.

Earlier samples rely on a direct VirtualAlloc call, while newer builds switch to an obfuscated ZwAllocateVirtualMemory invocation, with parameters dispersed and interleaved with junk instructions.

This is followed by a dense sequence of “write‑only” helper functions that populate the allocated region, creating a recognizable pattern of intensive small memory writes with little meaningful control flow.

In DLL form, pkr_mtsi supports multiple execution paths, including execution on load and via exported functions such as DllRegisterServer, enabling regsvr32‑based execution and persistence.

Mitigations

The intermediate stage is a modified UPX module with key markers deliberately stripped. Adversaries selectively remove DOS/PE headers, UPX magic values, and text resources as long as execution remains viable, complicating static signature‑based detection and automated unpacking.

Later generations of the packer introduce additional obfuscation: migration from plaintext API and DLL names to hash‑based resolution via PEB traversal, pervasive junk calls to GDI APIs to frustrate static and behavioral analysis, and custom routines to walk module lists and resolve exports.

Despite these evasions, the overall architecture remains stable: an initial pkr_mtsi layer, a degraded UPX intermediary, and a final malware payload.

Researchers also highlight several anti‑analysis and implementation quirks that defenders can weaponize.

The packer routinely calls debugger‑detection APIs such as IsDebuggerPresent and CheckRemoteDebuggerPresent, occasionally funneling execution into self‑referential infinite loops on detection a pattern that can be reliably hunted for in code and behavior.

More notably, repeated calls to NtProtectVirtualMemory use invalid protection flags, consistently producing the error STATUS_INVALID_PAGE_PROTECTION (0xC0000045).

This bug creates a high‑signal behavioral indicator in EDR telemetry, especially when correlated with the packer’s characteristic memory‑allocation‑plus‑dense‑writes pattern.

From an operational standpoint, these traits translate into concrete defensive opportunities. Security teams are advised to prioritize behavioral detections that focus on deterministic early‑stage allocation followed by a burst of tiny immediate‑value writes to a single region, obfuscated ZwAllocateVirtualMemory resolution.

For incident responders, familiarity with pkr_mtsi’s staged design and DLL‑based execution paths, including regsvr32‑driven loading, can accelerate triage, unpacking, and separation of packer behavior from the underlying payloads.

While the latest research primarily focuses on the packer itself, analysts indicate that deeper coverage of downstream UPX stages and associated payload families will follow in an upcoming report, as pkr_mtsi continues to underpin widespread malvertising‑driven intrusion chains across the Windows ecosystem.

Follow us on Google News, LinkedIn, and X to Get Instant Updates and Set GBH as a Preferred Source in Google.